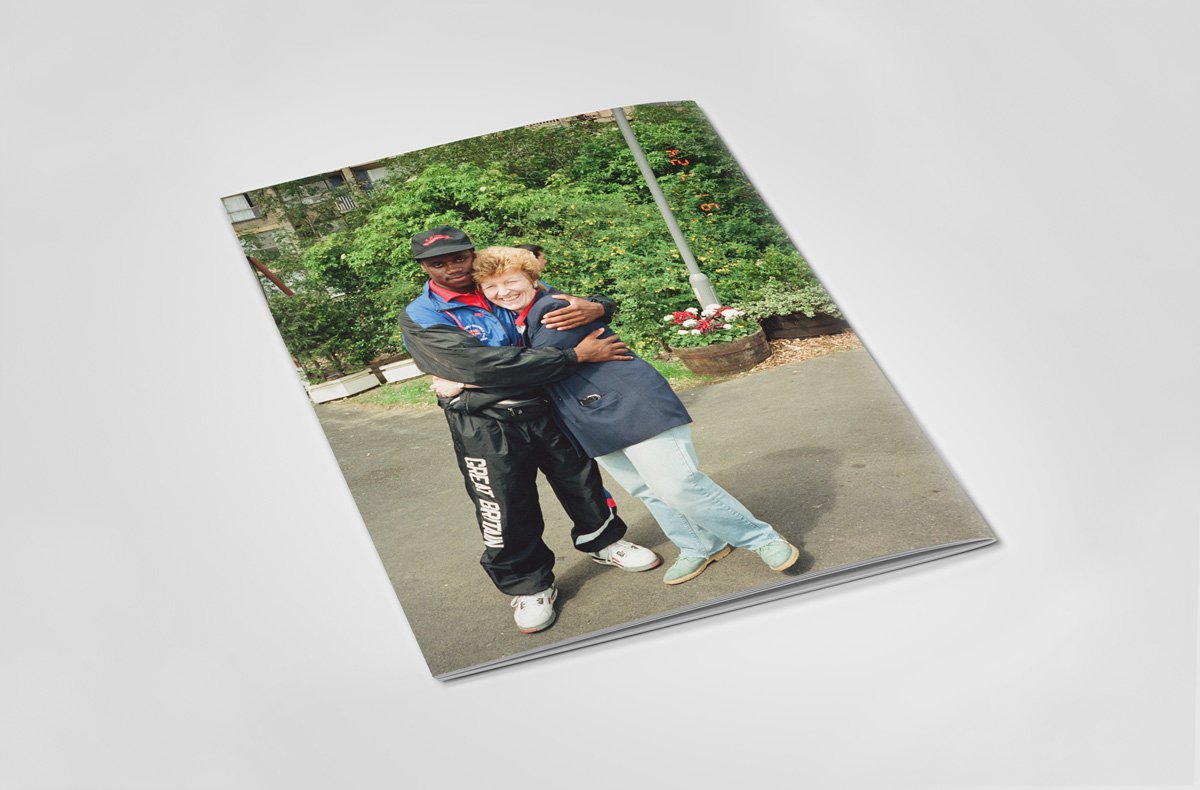

Linda Pitts — The World Student Games Sheffield 1991

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

The Spirit of ‘91

Around the turn of the millennium I landed my first job, at Don Valley Stadium, working as a gym assistant and general dogsbody for Sheffield International Venues, a council-run enterprise set up in 1988 ahead of the World Student Games. To save money I would walk two and a half miles from our terrace house in Firth Park, over Jenkin Hill near the Brendan Ingle boxing gym, and through Attercliffe, the old Industrial area, to get to work. I remember the ominous cries and thuds of heavy machinery, that always seemed both loud and distant, and echoed through a landscape that had seen better days. Then I’d enter this huge underused sporting facility in the middle of it all, which held its own echoes, though I loved the job and the building, which I thought of as a giant playground. The rubber floors looked like Lego, the support columns and beams were exposed in childish colours, and there was hardly anything to do, so I spent most of my time daydreaming, or racing around the cavernous interior and outdoor race track in a golf buggy pretending to complete various chores.

I couldn’t have put it into words then, but what all this amounts to is my coming of age at a time when Sheffield felt haunted by various, multilayered failed visions; of growing up in the wreckage of futures that never arrived. The modernism championed by John L Womersley, the postwar city planner who reimagined Sheffield after the Blitz, had by the end of the century largely fallen into decrepitude, left covered in graffiti or hidden behind late 80s postmodern cladding - brutalist buildings tarted up with primary colours and cheap ornamental gestures. Even during the New Labour boom time, Meadowhall Shopping Centre, erected on the grounds of an old steel works in 1990, was reminiscent of The Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, riddled with the ghosts of what came before, or what might have been. Now, those attempts at covering up the industrial decline are fading too; Don Valley stadium is no more, Meadowhall is a shadow of its former self, and any infrastructure in those once vibrant 80s hues looks ghostly and weather worn.

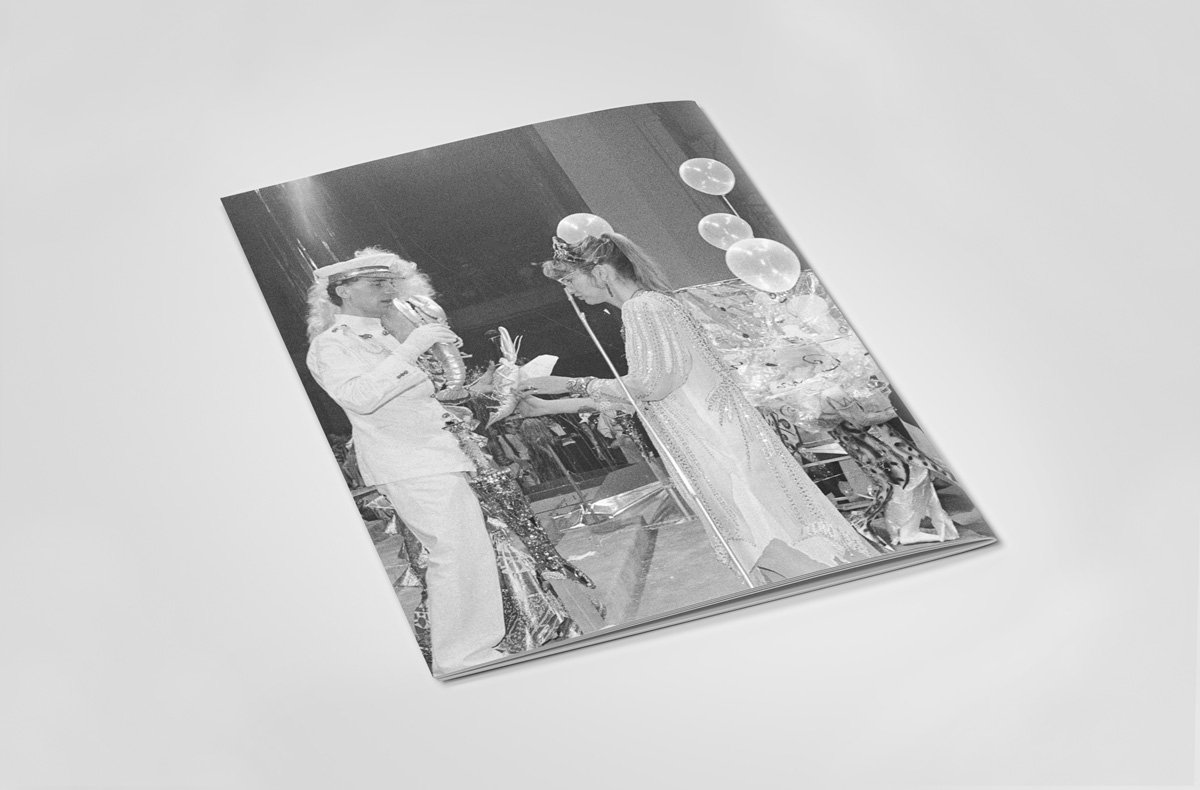

But these images taken by my Mum, Linda, when she worked as a volunteer for the World Student Games, take me back to a moment of optimism. We’d just returned from a brief and utterly bonkers stint living in Japan at the height of its bubble economy in 1990, the year in which Nelson Mandela was released from prison, Germany was reunified, and the UK grew closer to Europe than ever before, set to join the EEC by 1992. Sheffield’s hosting of the games was controversial even at the time (the huge debt accrued only paid off this year), but part of an attempt to reimagine a city - whose industrial heritage had been decimated during Thatcher’s reign - as a city of sport and leisure. I was there with my Mum as a child, and remember the buzzing international atmosphere around the student village, housed in a now demolished section of the brutalist Hyde Park Flats. For my family, having just returned from affluent Tokyo, seeing the world come to Sheffield was a welcome reminder of something bigger than our struggling hometown, and signalled a future of global connectedness. Yet it still amazes me, as I look at these photos, that they were taken on the same camera my parents used to take images of the neon-lit futurism in Japan only a year earlier, and calls to mind the words of Cyberpunk novelist William Gibson; “the future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed”. 1991 was the year Gibson wrote his novel “The Difference Engine,” which explores this very idea. What is left, then, is a reminder that the relationship between working class communities and globalisation has always been complex and often ambivalent.

Johny Pitts, 2024

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

The Spirit of ‘91

Around the turn of the millennium I landed my first job, at Don Valley Stadium, working as a gym assistant and general dogsbody for Sheffield International Venues, a council-run enterprise set up in 1988 ahead of the World Student Games. To save money I would walk two and a half miles from our terrace house in Firth Park, over Jenkin Hill near the Brendan Ingle boxing gym, and through Attercliffe, the old Industrial area, to get to work. I remember the ominous cries and thuds of heavy machinery, that always seemed both loud and distant, and echoed through a landscape that had seen better days. Then I’d enter this huge underused sporting facility in the middle of it all, which held its own echoes, though I loved the job and the building, which I thought of as a giant playground. The rubber floors looked like Lego, the support columns and beams were exposed in childish colours, and there was hardly anything to do, so I spent most of my time daydreaming, or racing around the cavernous interior and outdoor race track in a golf buggy pretending to complete various chores.

I couldn’t have put it into words then, but what all this amounts to is my coming of age at a time when Sheffield felt haunted by various, multilayered failed visions; of growing up in the wreckage of futures that never arrived. The modernism championed by John L Womersley, the postwar city planner who reimagined Sheffield after the Blitz, had by the end of the century largely fallen into decrepitude, left covered in graffiti or hidden behind late 80s postmodern cladding - brutalist buildings tarted up with primary colours and cheap ornamental gestures. Even during the New Labour boom time, Meadowhall Shopping Centre, erected on the grounds of an old steel works in 1990, was reminiscent of The Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, riddled with the ghosts of what came before, or what might have been. Now, those attempts at covering up the industrial decline are fading too; Don Valley stadium is no more, Meadowhall is a shadow of its former self, and any infrastructure in those once vibrant 80s hues looks ghostly and weather worn.

But these images taken by my Mum, Linda, when she worked as a volunteer for the World Student Games, take me back to a moment of optimism. We’d just returned from a brief and utterly bonkers stint living in Japan at the height of its bubble economy in 1990, the year in which Nelson Mandela was released from prison, Germany was reunified, and the UK grew closer to Europe than ever before, set to join the EEC by 1992. Sheffield’s hosting of the games was controversial even at the time (the huge debt accrued only paid off this year), but part of an attempt to reimagine a city - whose industrial heritage had been decimated during Thatcher’s reign - as a city of sport and leisure. I was there with my Mum as a child, and remember the buzzing international atmosphere around the student village, housed in a now demolished section of the brutalist Hyde Park Flats. For my family, having just returned from affluent Tokyo, seeing the world come to Sheffield was a welcome reminder of something bigger than our struggling hometown, and signalled a future of global connectedness. Yet it still amazes me, as I look at these photos, that they were taken on the same camera my parents used to take images of the neon-lit futurism in Japan only a year earlier, and calls to mind the words of Cyberpunk novelist William Gibson; “the future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed”. 1991 was the year Gibson wrote his novel “The Difference Engine,” which explores this very idea. What is left, then, is a reminder that the relationship between working class communities and globalisation has always been complex and often ambivalent.

Johny Pitts, 2024

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

The Spirit of ‘91

Around the turn of the millennium I landed my first job, at Don Valley Stadium, working as a gym assistant and general dogsbody for Sheffield International Venues, a council-run enterprise set up in 1988 ahead of the World Student Games. To save money I would walk two and a half miles from our terrace house in Firth Park, over Jenkin Hill near the Brendan Ingle boxing gym, and through Attercliffe, the old Industrial area, to get to work. I remember the ominous cries and thuds of heavy machinery, that always seemed both loud and distant, and echoed through a landscape that had seen better days. Then I’d enter this huge underused sporting facility in the middle of it all, which held its own echoes, though I loved the job and the building, which I thought of as a giant playground. The rubber floors looked like Lego, the support columns and beams were exposed in childish colours, and there was hardly anything to do, so I spent most of my time daydreaming, or racing around the cavernous interior and outdoor race track in a golf buggy pretending to complete various chores.

I couldn’t have put it into words then, but what all this amounts to is my coming of age at a time when Sheffield felt haunted by various, multilayered failed visions; of growing up in the wreckage of futures that never arrived. The modernism championed by John L Womersley, the postwar city planner who reimagined Sheffield after the Blitz, had by the end of the century largely fallen into decrepitude, left covered in graffiti or hidden behind late 80s postmodern cladding - brutalist buildings tarted up with primary colours and cheap ornamental gestures. Even during the New Labour boom time, Meadowhall Shopping Centre, erected on the grounds of an old steel works in 1990, was reminiscent of The Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, riddled with the ghosts of what came before, or what might have been. Now, those attempts at covering up the industrial decline are fading too; Don Valley stadium is no more, Meadowhall is a shadow of its former self, and any infrastructure in those once vibrant 80s hues looks ghostly and weather worn.

But these images taken by my Mum, Linda, when she worked as a volunteer for the World Student Games, take me back to a moment of optimism. We’d just returned from a brief and utterly bonkers stint living in Japan at the height of its bubble economy in 1990, the year in which Nelson Mandela was released from prison, Germany was reunified, and the UK grew closer to Europe than ever before, set to join the EEC by 1992. Sheffield’s hosting of the games was controversial even at the time (the huge debt accrued only paid off this year), but part of an attempt to reimagine a city - whose industrial heritage had been decimated during Thatcher’s reign - as a city of sport and leisure. I was there with my Mum as a child, and remember the buzzing international atmosphere around the student village, housed in a now demolished section of the brutalist Hyde Park Flats. For my family, having just returned from affluent Tokyo, seeing the world come to Sheffield was a welcome reminder of something bigger than our struggling hometown, and signalled a future of global connectedness. Yet it still amazes me, as I look at these photos, that they were taken on the same camera my parents used to take images of the neon-lit futurism in Japan only a year earlier, and calls to mind the words of Cyberpunk novelist William Gibson; “the future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed”. 1991 was the year Gibson wrote his novel “The Difference Engine,” which explores this very idea. What is left, then, is a reminder that the relationship between working class communities and globalisation has always been complex and often ambivalent.

Johny Pitts, 2024