LB — Kingston upon Hull 1970s

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

second print

available as part of a Luis Bustamante three book bundle, here

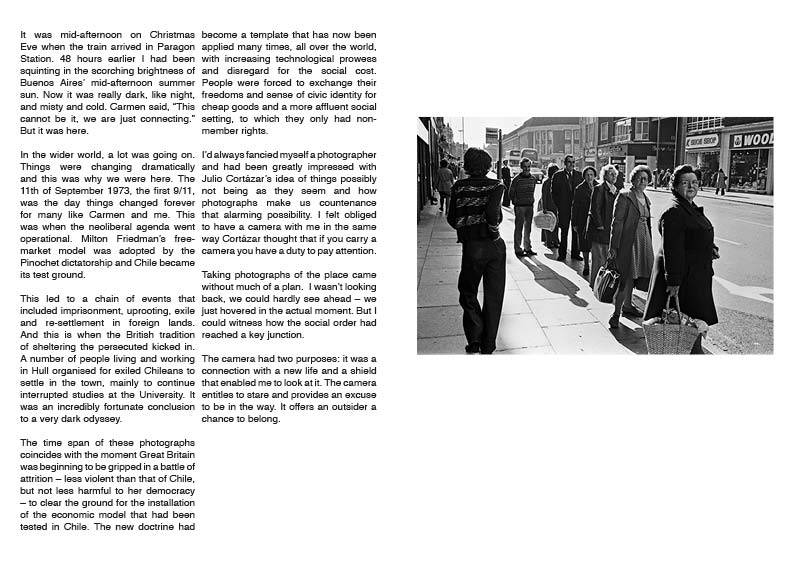

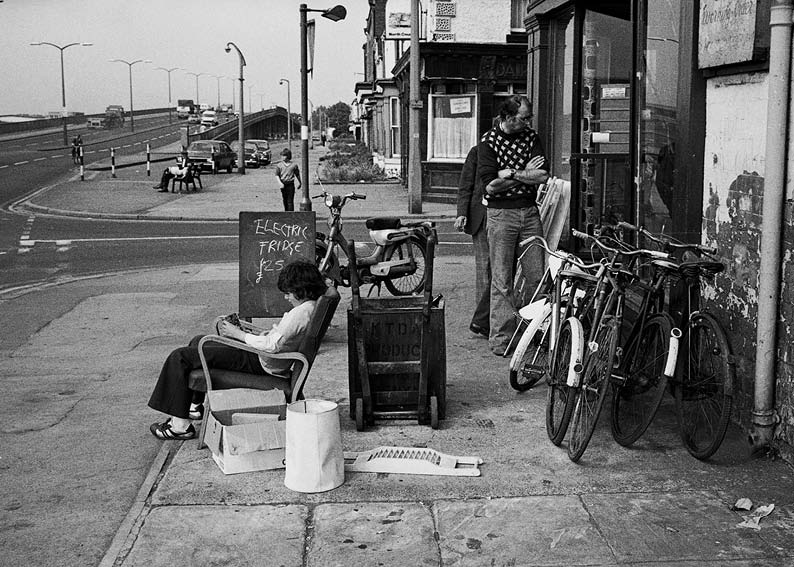

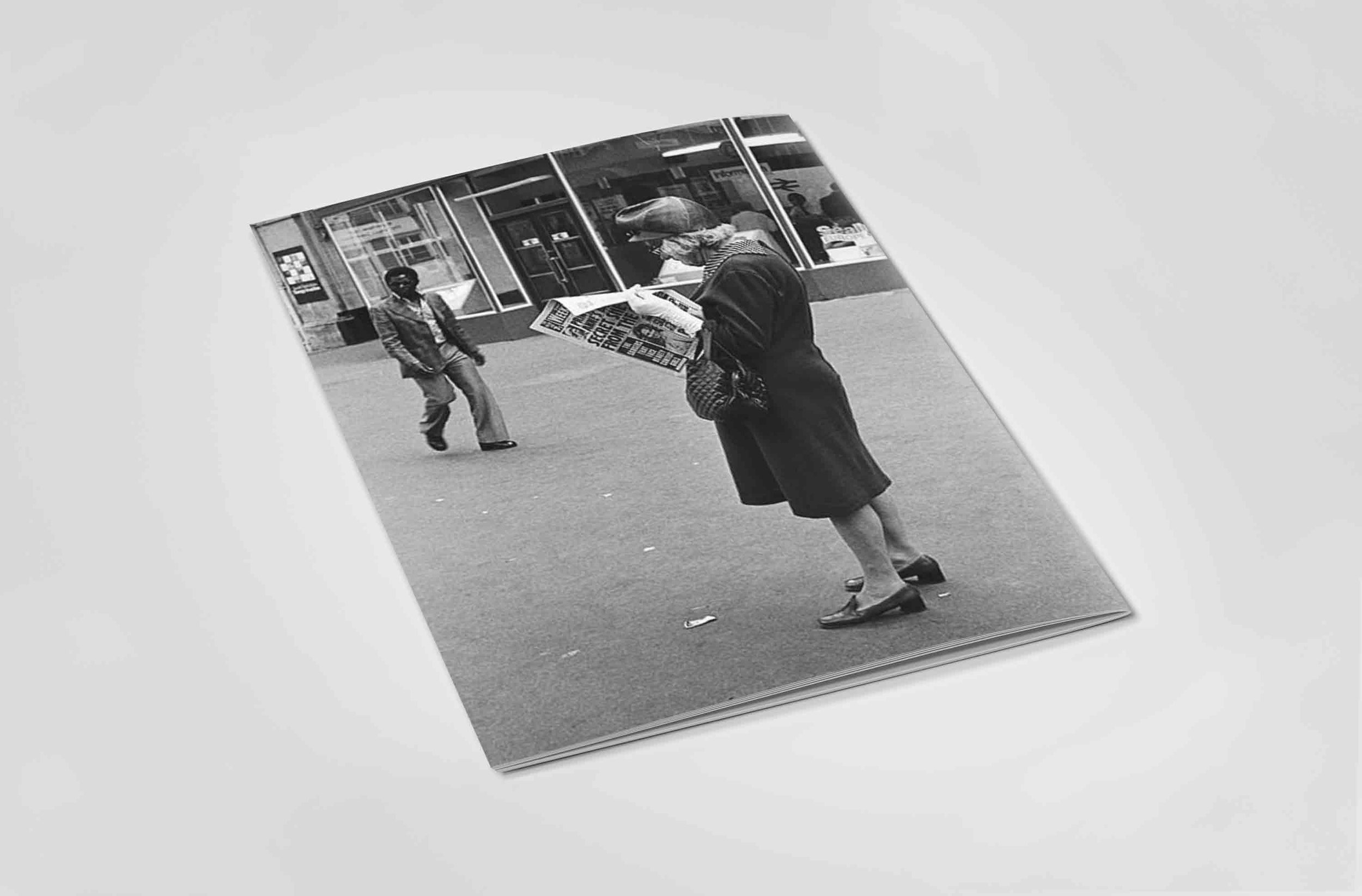

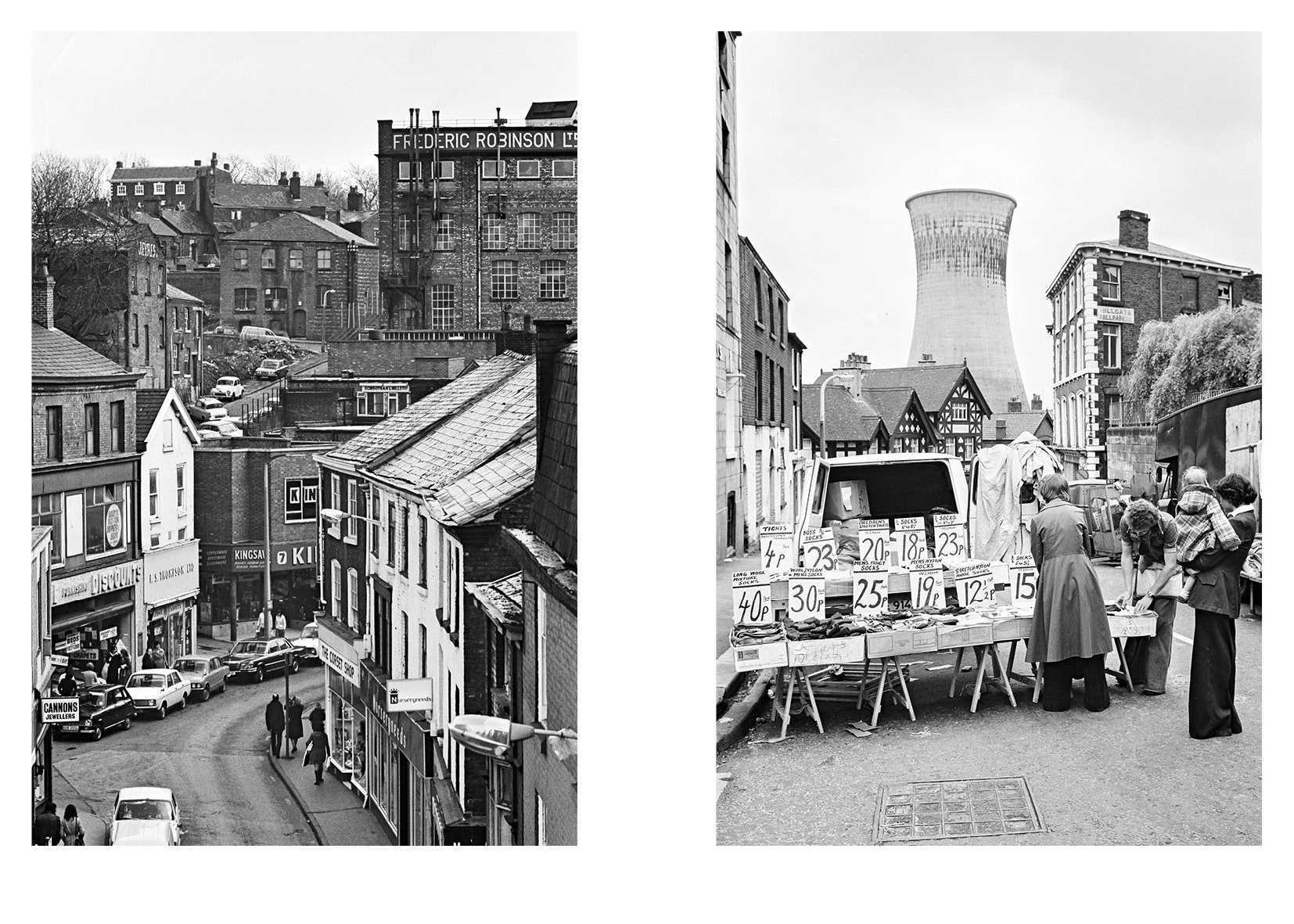

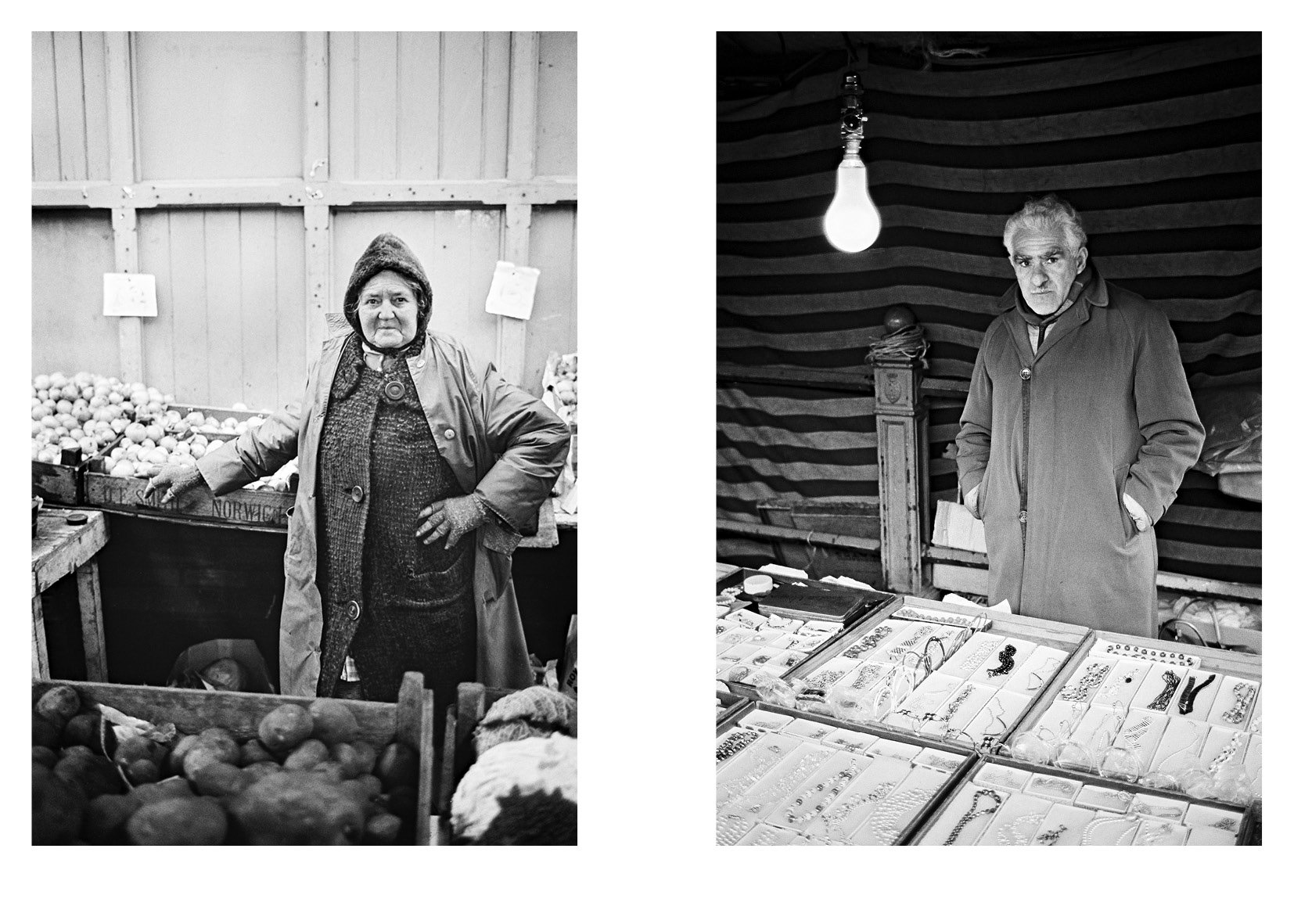

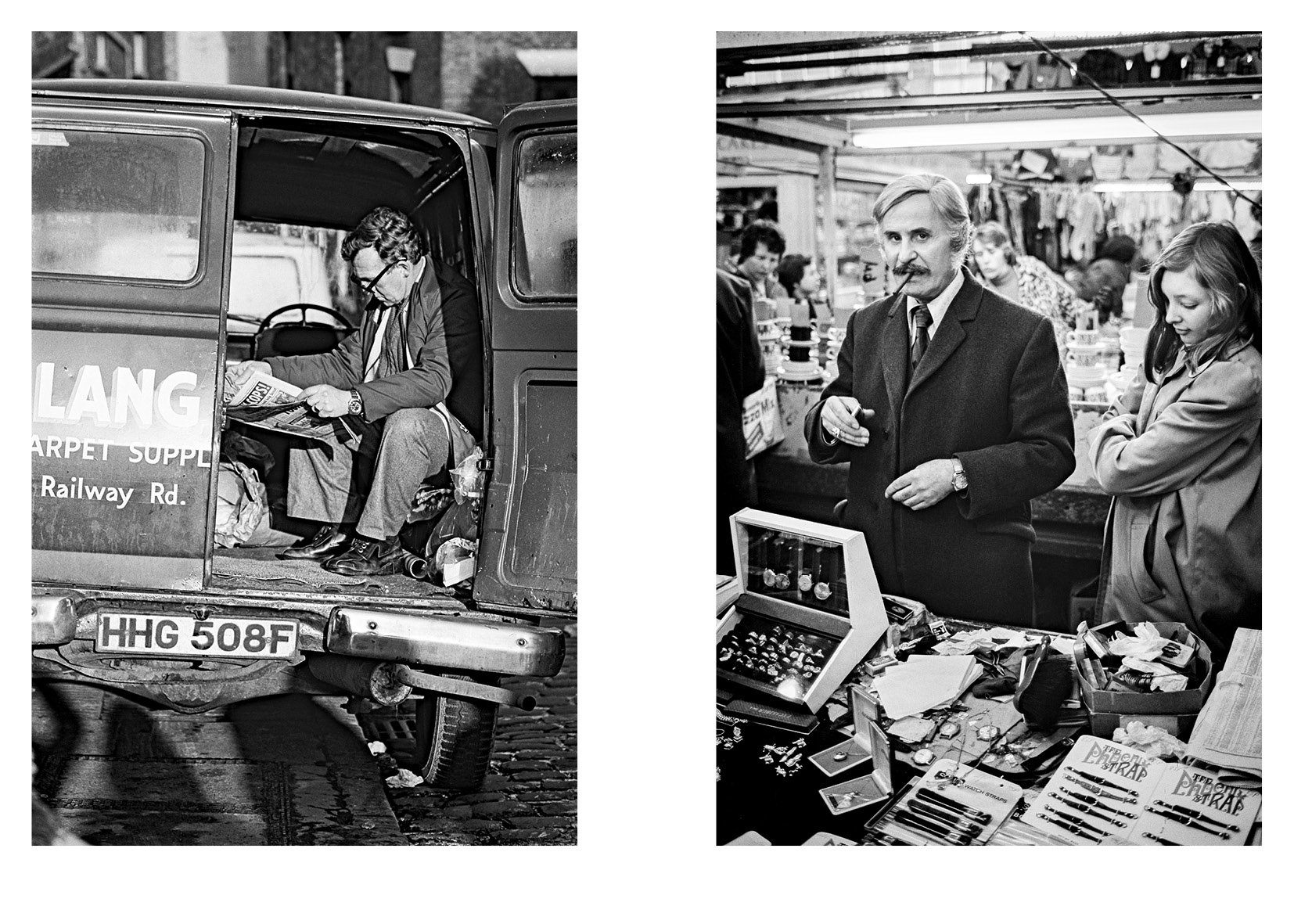

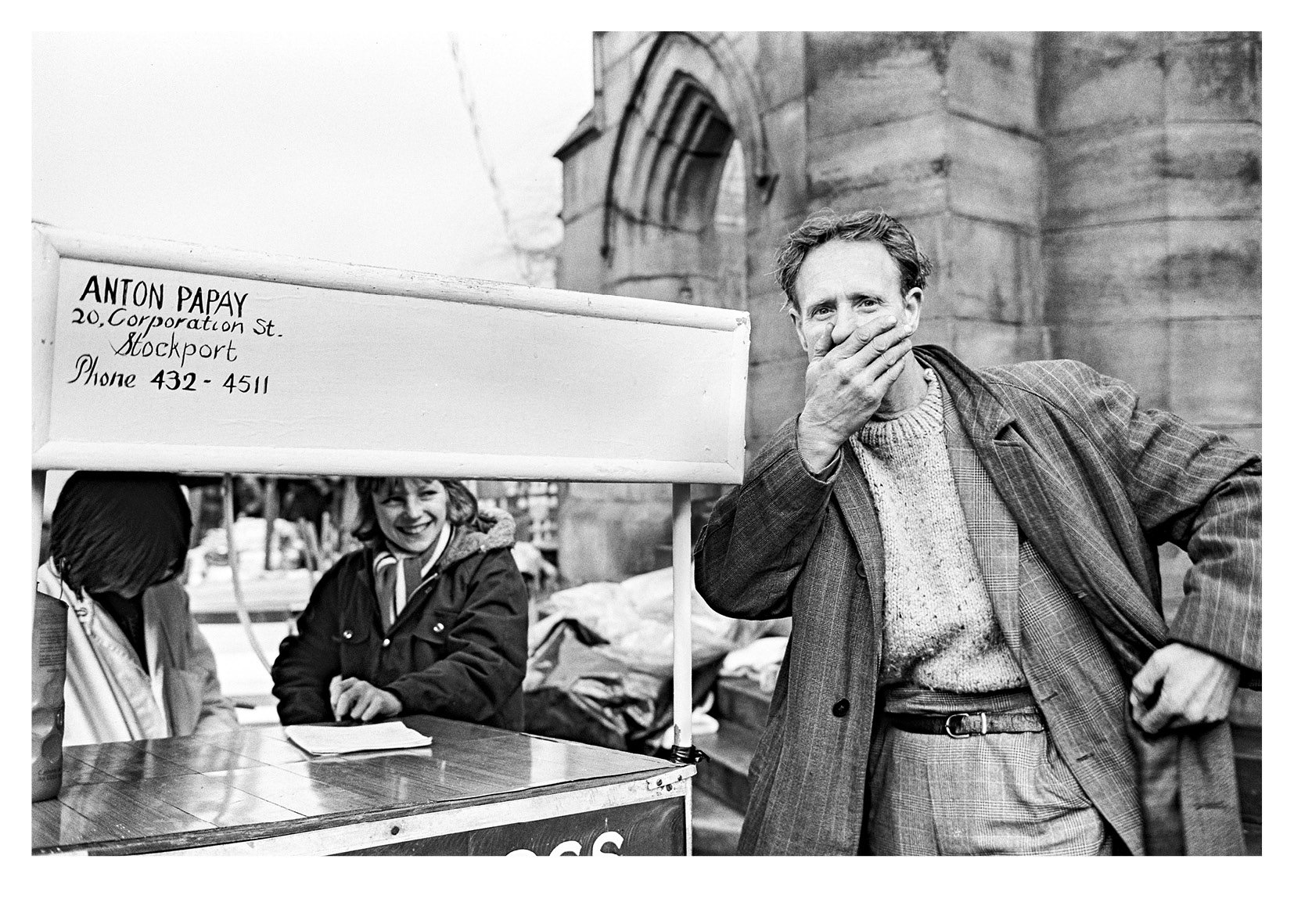

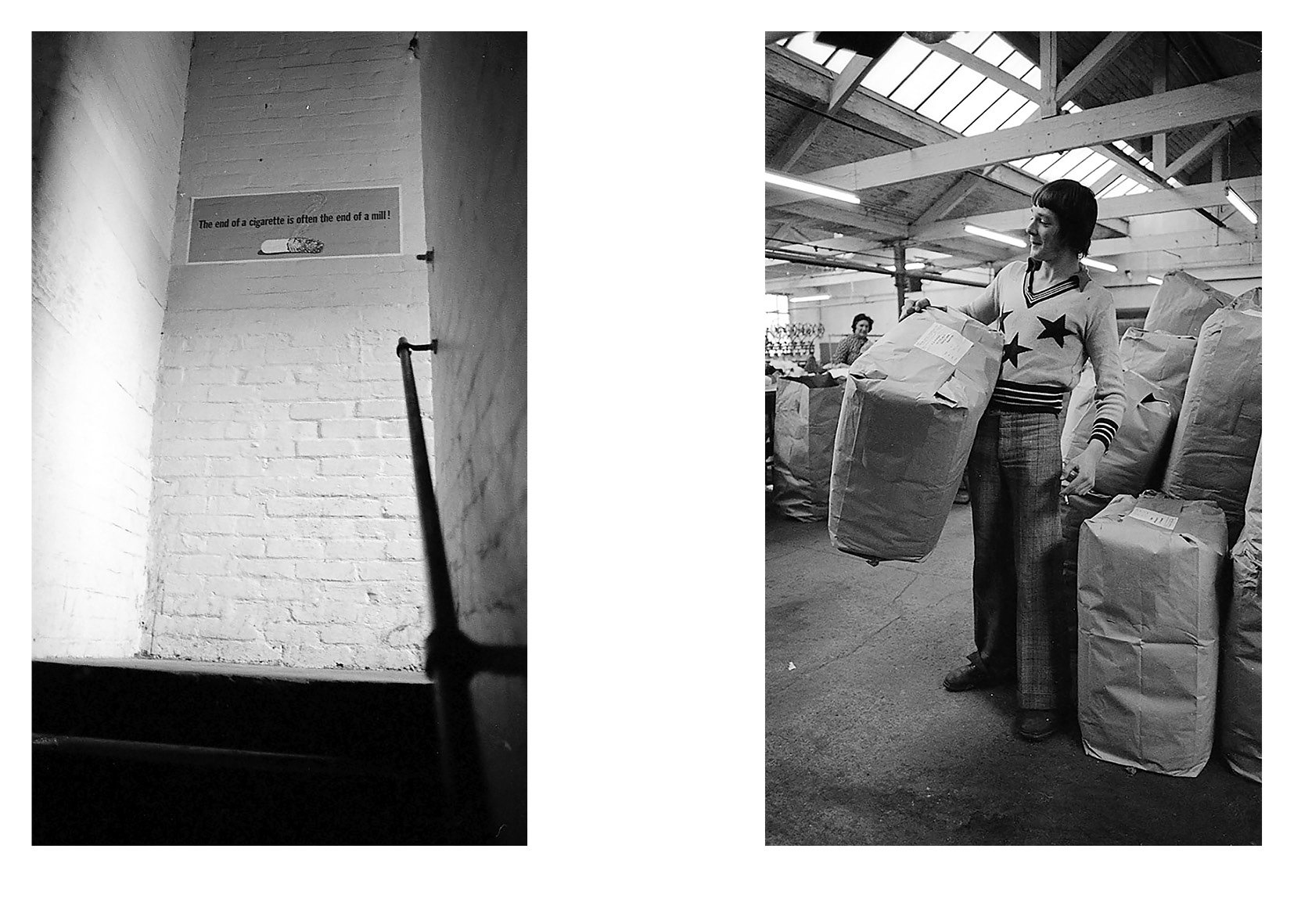

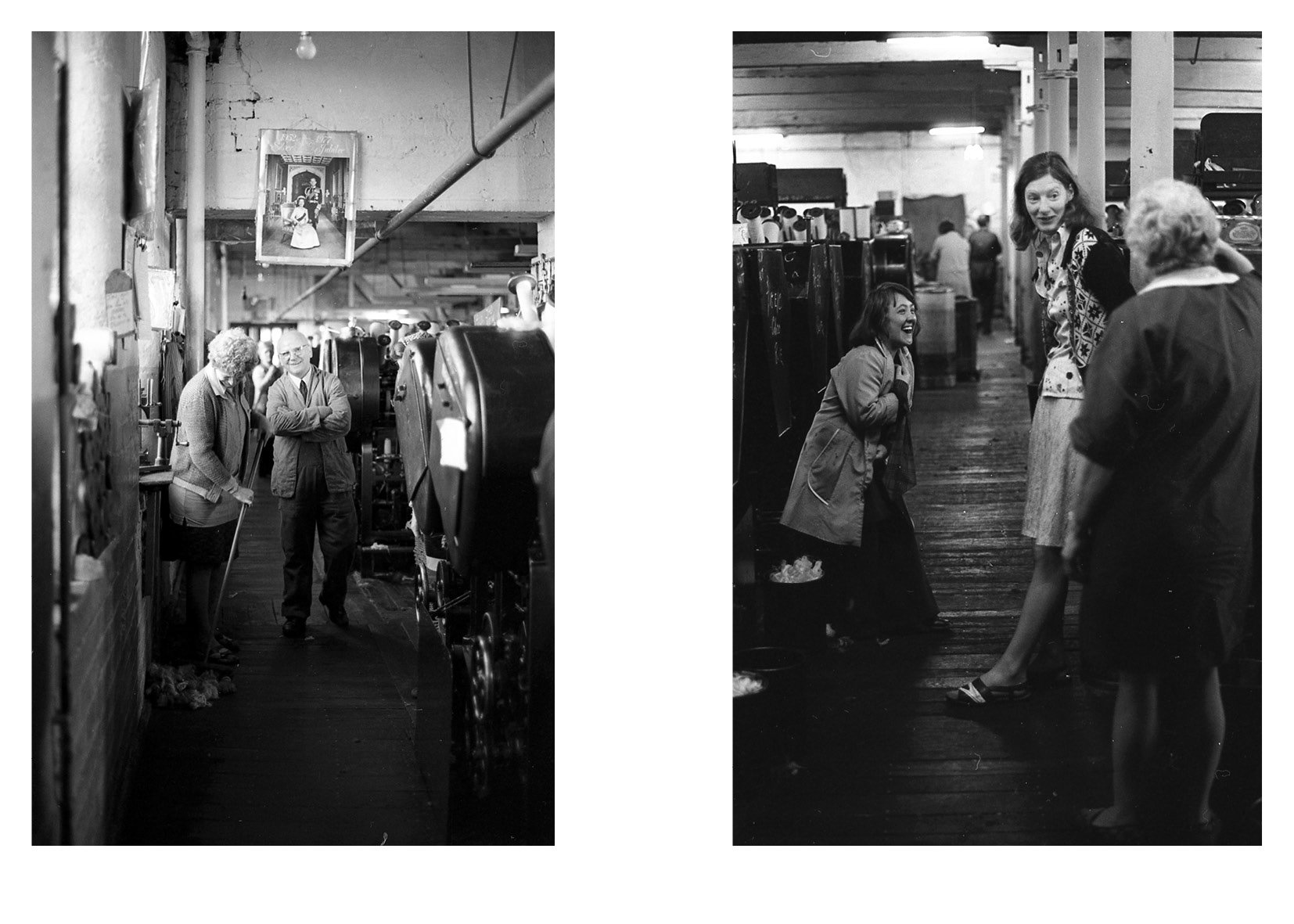

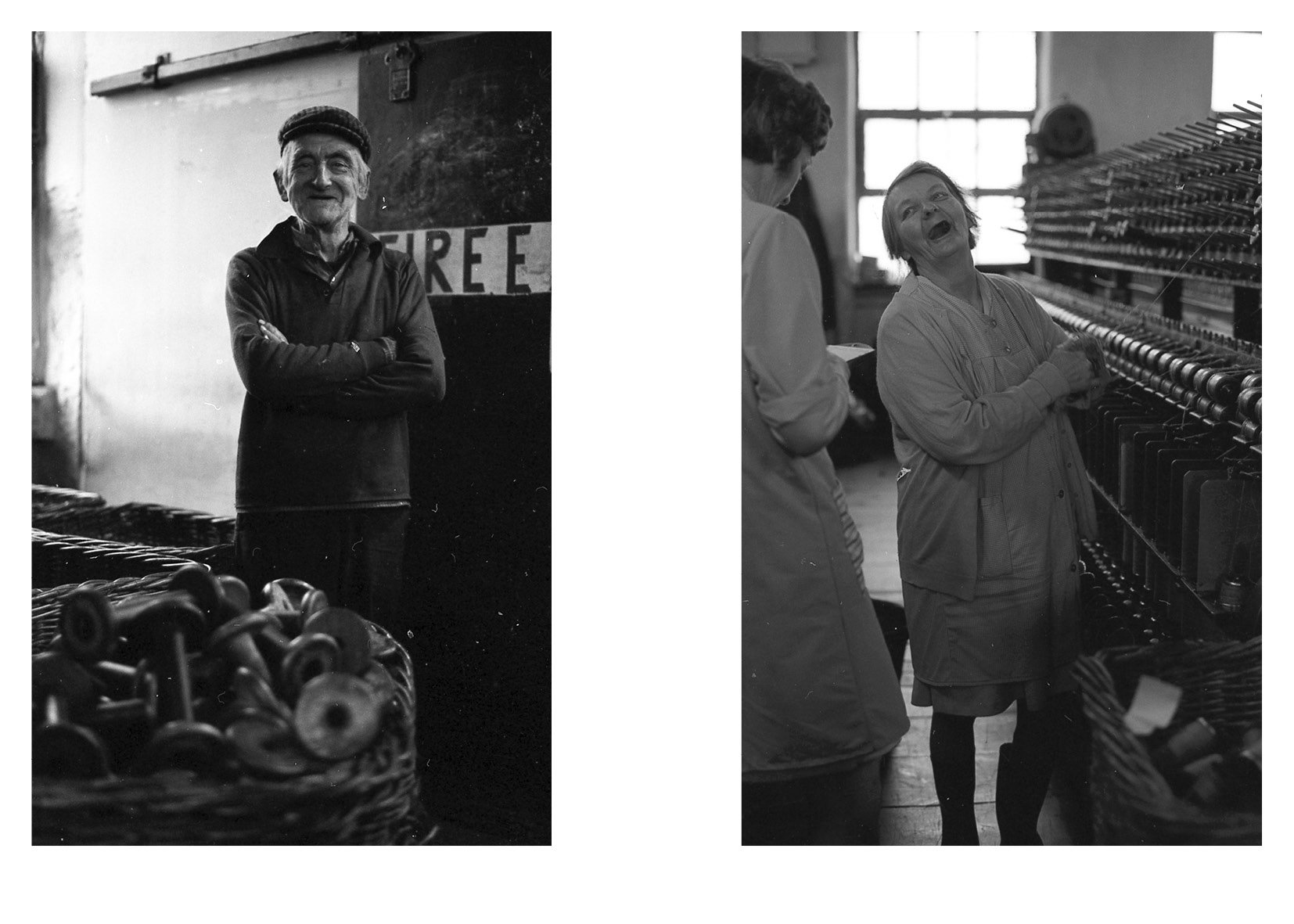

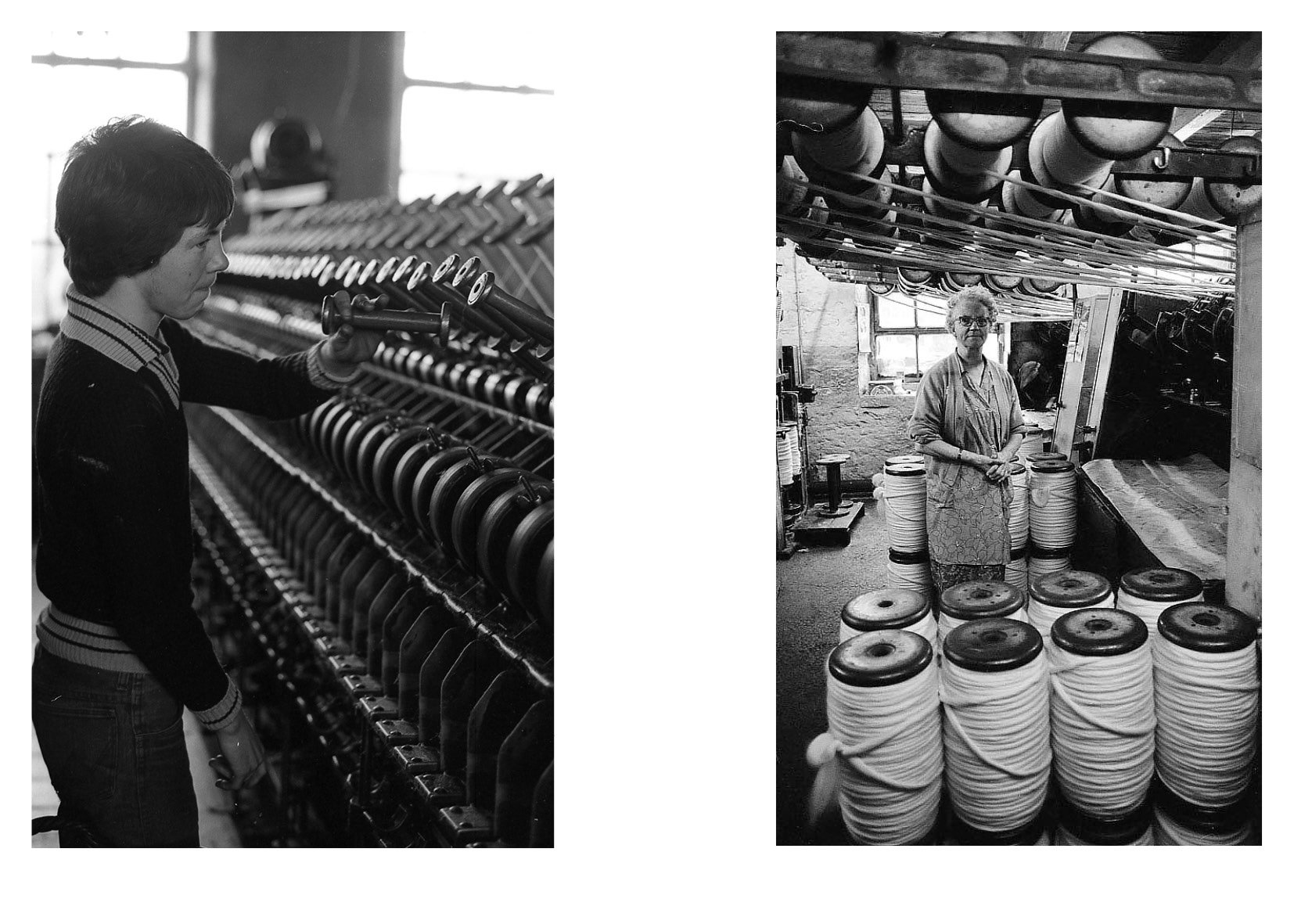

It was mid-afternoon on Christmas Eve when the train arrived in Paragon Station. 48 hours earlier I had been squinting in the scorching brightness of Buenos Aires’ mid-afternoon summer sun. Now it was really dark, like night, and misty and cold. Carmen said, “This cannot be it, we are just connecting.” But it was here.

In the wider world, a lot was going on. Things were changing dramatically and this was why we were here. The 11th of September 1973, the first 9/11, was the day things changed forever for many like Carmen and me. This was when the neoliberal agenda went operational. Milton Friedman’s free-market model was adopted by the Pinochet dictatorship and Chile became its test ground.

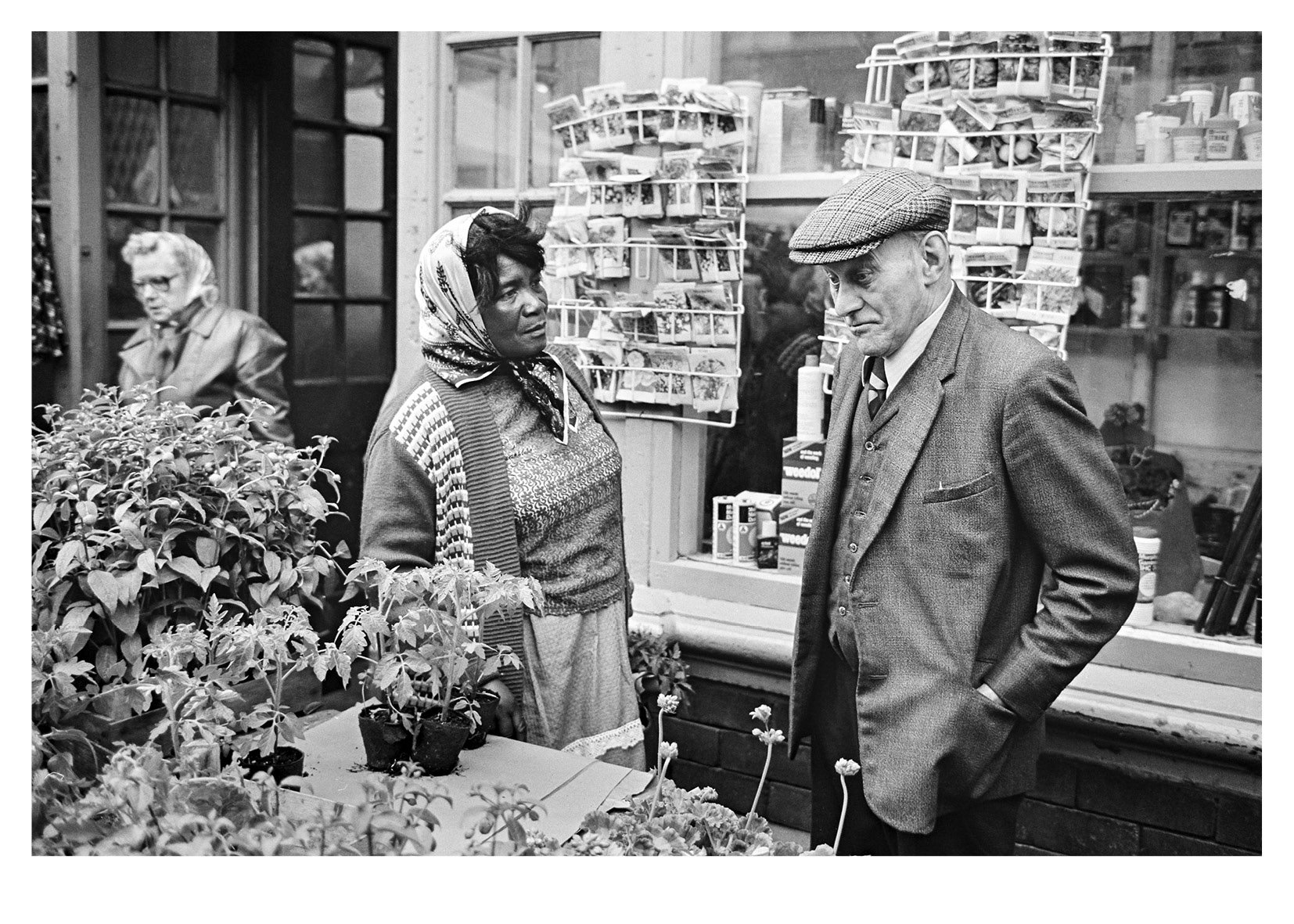

This led to a chain of events that included imprisonment, uprooting, exile and re-settlement in foreign lands. And this is when the British tradition of sheltering the persecuted kicked in. A number of people living and working in Hull organised for exiled Chileans to settle in the town, mainly to continue interrupted studies at the University. It was an incredibly fortunate conclusion to a very dark odyssey.

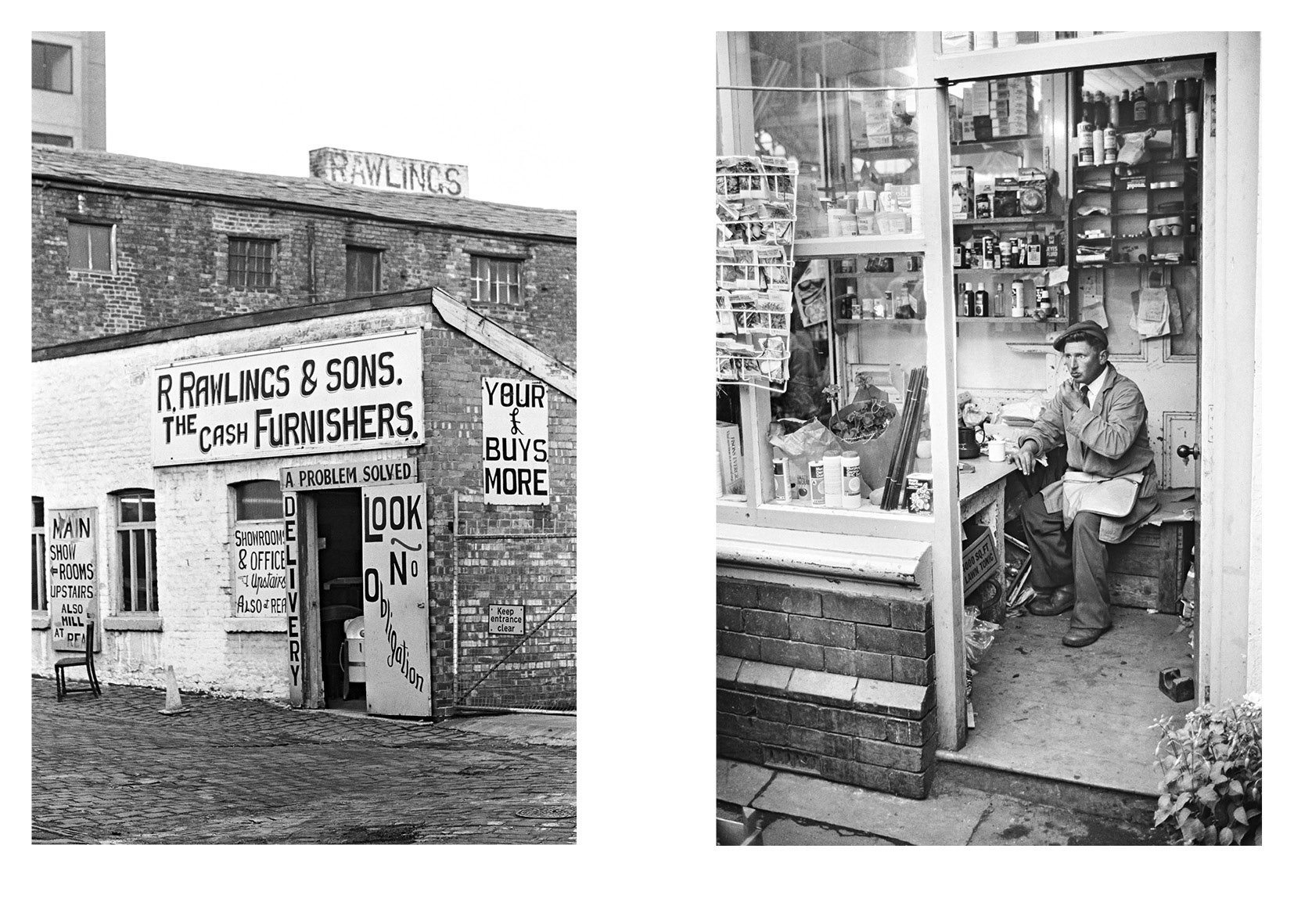

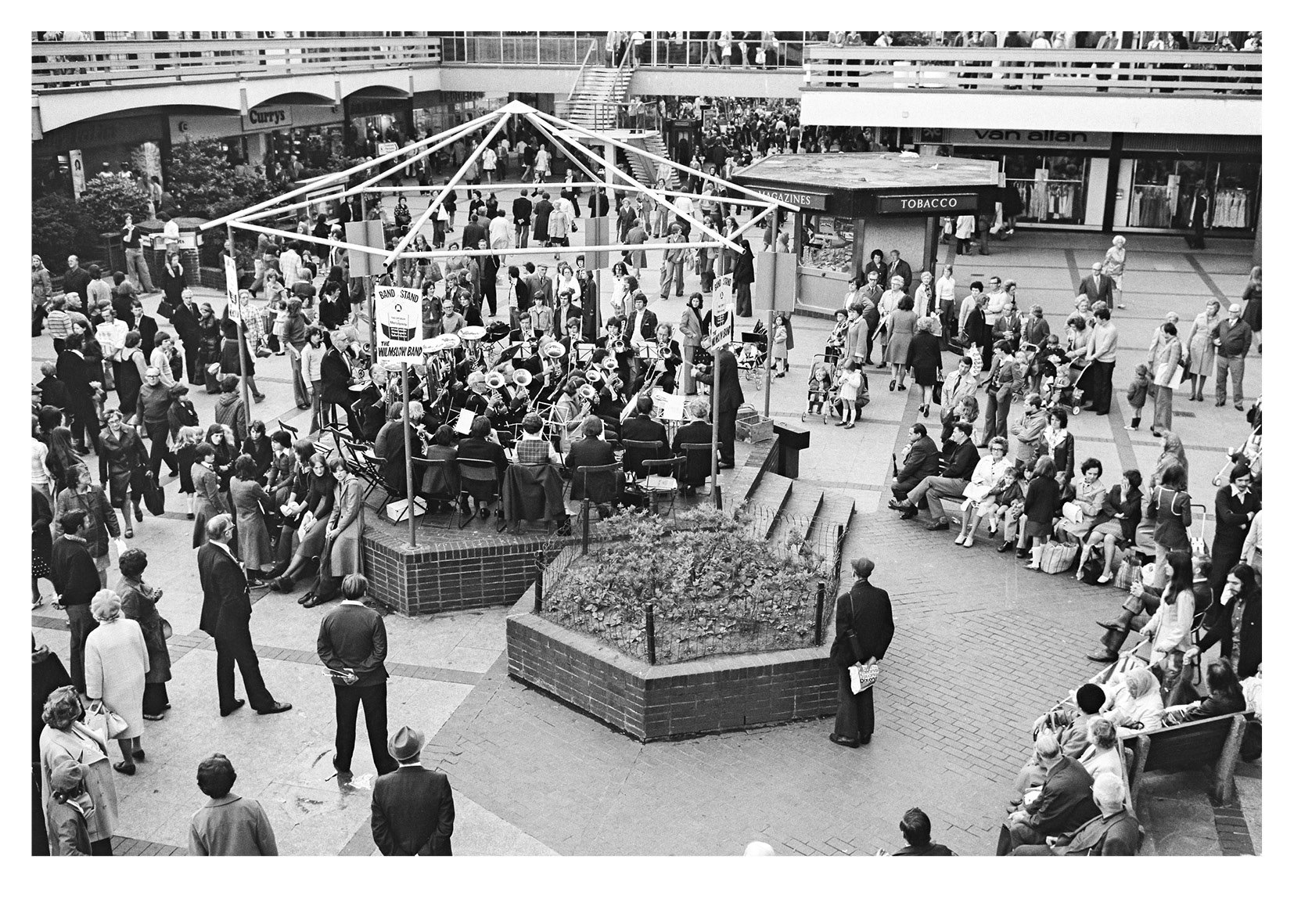

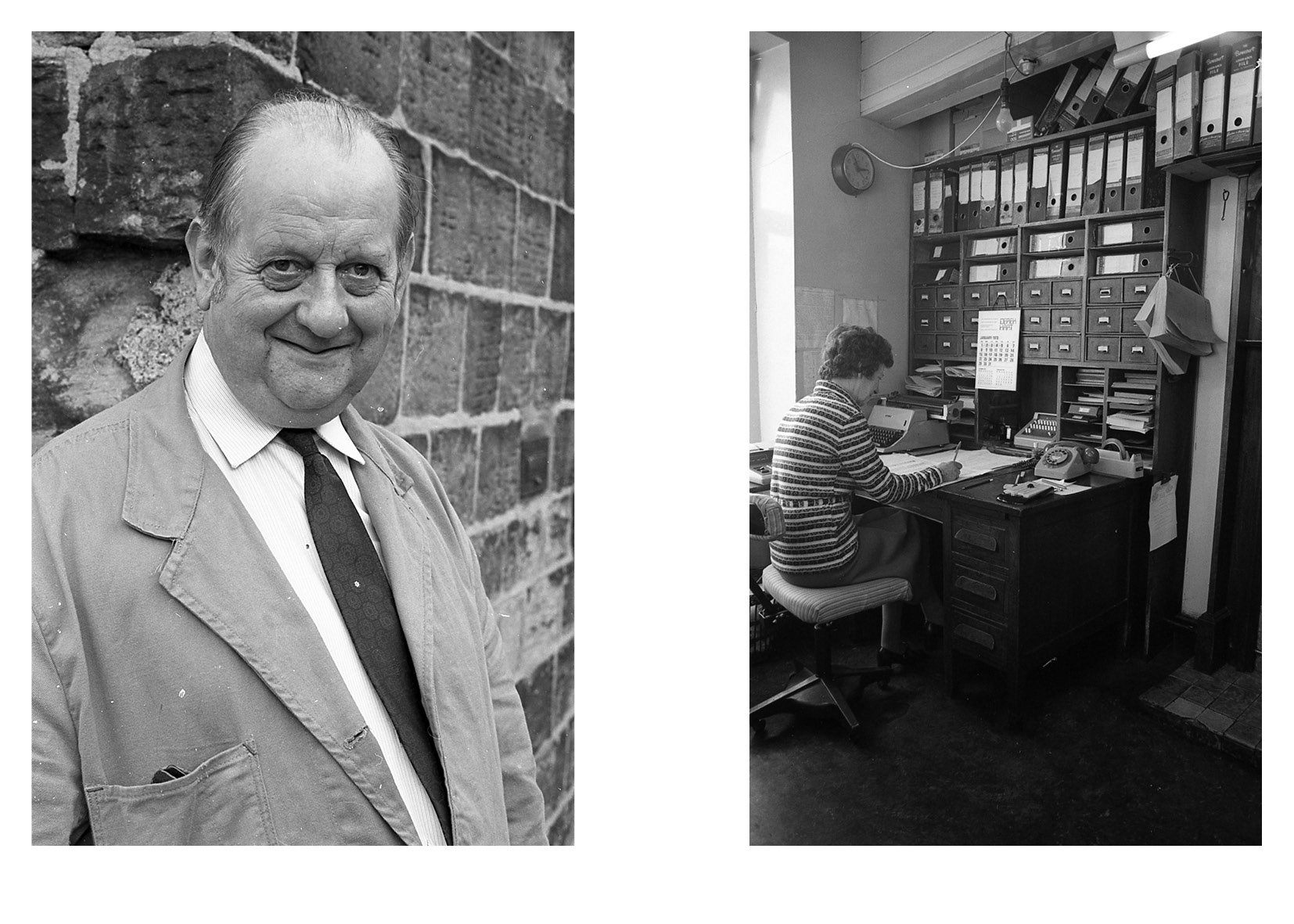

The time span of these photographs coincides with the moment Great Britain was beginning to be gripped in a battle of attrition – less violent than that of Chile, but not less harmful to her democracy – to clear the ground for the installation of the economic model that had been tested in Chile. The new doctrine had become a template that has now been applied many times, all over the world, with increasing technological prowess and disregard for the social cost. People were forced to exchange their freedoms and sense of civic identity for cheap goods and a more affluent social setting, to which they only had non-member rights.

I’d always fancied myself a photographer and had been greatly impressed with Julio Cortázar’s idea of things possibly not being as they seem and how photographs make us countenance that alarming possibility. I felt obliged to have a camera with me in the same way Cortázar thought that if you carry a camera you have a duty to pay attention.

Taking photographs of the place came without much of a plan. I wasn’t looking back, we could hardly see ahead – we just hovered in the actual moment. But I could witness how the social order had reached a key junction.

The camera had two purposes: it was a connection with a new life and a shield that enabled me to look at it. The camera entitles to stare and provides an excuse to be in the way. It offers an outsider a chance to belong.

Luis Bustamante

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

second print

available as part of a Luis Bustamante three book bundle, here

It was mid-afternoon on Christmas Eve when the train arrived in Paragon Station. 48 hours earlier I had been squinting in the scorching brightness of Buenos Aires’ mid-afternoon summer sun. Now it was really dark, like night, and misty and cold. Carmen said, “This cannot be it, we are just connecting.” But it was here.

In the wider world, a lot was going on. Things were changing dramatically and this was why we were here. The 11th of September 1973, the first 9/11, was the day things changed forever for many like Carmen and me. This was when the neoliberal agenda went operational. Milton Friedman’s free-market model was adopted by the Pinochet dictatorship and Chile became its test ground.

This led to a chain of events that included imprisonment, uprooting, exile and re-settlement in foreign lands. And this is when the British tradition of sheltering the persecuted kicked in. A number of people living and working in Hull organised for exiled Chileans to settle in the town, mainly to continue interrupted studies at the University. It was an incredibly fortunate conclusion to a very dark odyssey.

The time span of these photographs coincides with the moment Great Britain was beginning to be gripped in a battle of attrition – less violent than that of Chile, but not less harmful to her democracy – to clear the ground for the installation of the economic model that had been tested in Chile. The new doctrine had become a template that has now been applied many times, all over the world, with increasing technological prowess and disregard for the social cost. People were forced to exchange their freedoms and sense of civic identity for cheap goods and a more affluent social setting, to which they only had non-member rights.

I’d always fancied myself a photographer and had been greatly impressed with Julio Cortázar’s idea of things possibly not being as they seem and how photographs make us countenance that alarming possibility. I felt obliged to have a camera with me in the same way Cortázar thought that if you carry a camera you have a duty to pay attention.

Taking photographs of the place came without much of a plan. I wasn’t looking back, we could hardly see ahead – we just hovered in the actual moment. But I could witness how the social order had reached a key junction.

The camera had two purposes: it was a connection with a new life and a shield that enabled me to look at it. The camera entitles to stare and provides an excuse to be in the way. It offers an outsider a chance to belong.

Luis Bustamante

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

second print

available as part of a Luis Bustamante three book bundle, here

It was mid-afternoon on Christmas Eve when the train arrived in Paragon Station. 48 hours earlier I had been squinting in the scorching brightness of Buenos Aires’ mid-afternoon summer sun. Now it was really dark, like night, and misty and cold. Carmen said, “This cannot be it, we are just connecting.” But it was here.

In the wider world, a lot was going on. Things were changing dramatically and this was why we were here. The 11th of September 1973, the first 9/11, was the day things changed forever for many like Carmen and me. This was when the neoliberal agenda went operational. Milton Friedman’s free-market model was adopted by the Pinochet dictatorship and Chile became its test ground.

This led to a chain of events that included imprisonment, uprooting, exile and re-settlement in foreign lands. And this is when the British tradition of sheltering the persecuted kicked in. A number of people living and working in Hull organised for exiled Chileans to settle in the town, mainly to continue interrupted studies at the University. It was an incredibly fortunate conclusion to a very dark odyssey.

The time span of these photographs coincides with the moment Great Britain was beginning to be gripped in a battle of attrition – less violent than that of Chile, but not less harmful to her democracy – to clear the ground for the installation of the economic model that had been tested in Chile. The new doctrine had become a template that has now been applied many times, all over the world, with increasing technological prowess and disregard for the social cost. People were forced to exchange their freedoms and sense of civic identity for cheap goods and a more affluent social setting, to which they only had non-member rights.

I’d always fancied myself a photographer and had been greatly impressed with Julio Cortázar’s idea of things possibly not being as they seem and how photographs make us countenance that alarming possibility. I felt obliged to have a camera with me in the same way Cortázar thought that if you carry a camera you have a duty to pay attention.

Taking photographs of the place came without much of a plan. I wasn’t looking back, we could hardly see ahead – we just hovered in the actual moment. But I could witness how the social order had reached a key junction.

The camera had two purposes: it was a connection with a new life and a shield that enabled me to look at it. The camera entitles to stare and provides an excuse to be in the way. It offers an outsider a chance to belong.

Luis Bustamante