Image 1 of 19

Image 1 of 19

Image 2 of 19

Image 2 of 19

Image 3 of 19

Image 3 of 19

Image 4 of 19

Image 4 of 19

Image 5 of 19

Image 5 of 19

Image 6 of 19

Image 6 of 19

Image 7 of 19

Image 7 of 19

Image 8 of 19

Image 8 of 19

Image 9 of 19

Image 9 of 19

Image 10 of 19

Image 10 of 19

Image 11 of 19

Image 11 of 19

Image 12 of 19

Image 12 of 19

Image 13 of 19

Image 13 of 19

Image 14 of 19

Image 14 of 19

Image 15 of 19

Image 15 of 19

Image 16 of 19

Image 16 of 19

Image 17 of 19

Image 17 of 19

Image 18 of 19

Image 18 of 19

Image 19 of 19

Image 19 of 19

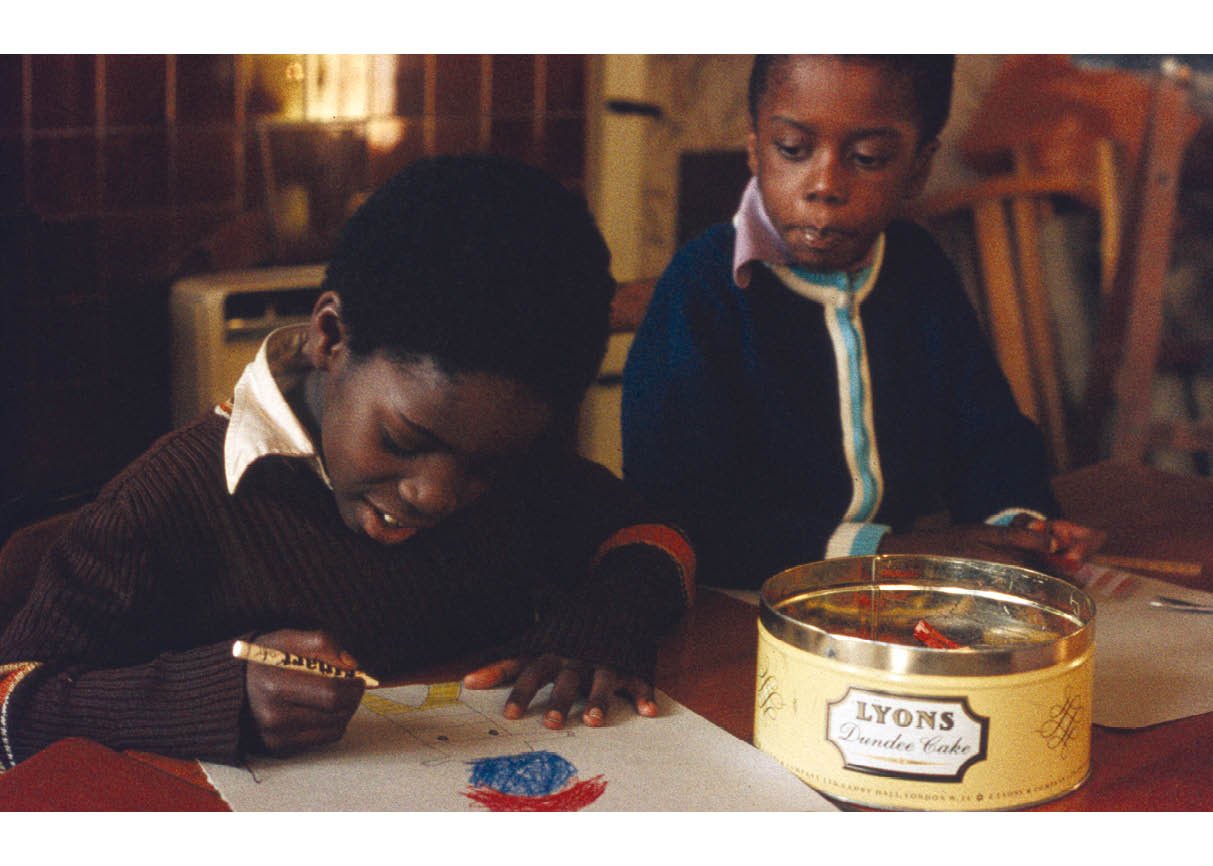

Chris Richards — West Indian Supplementary Service. London 1974–1975

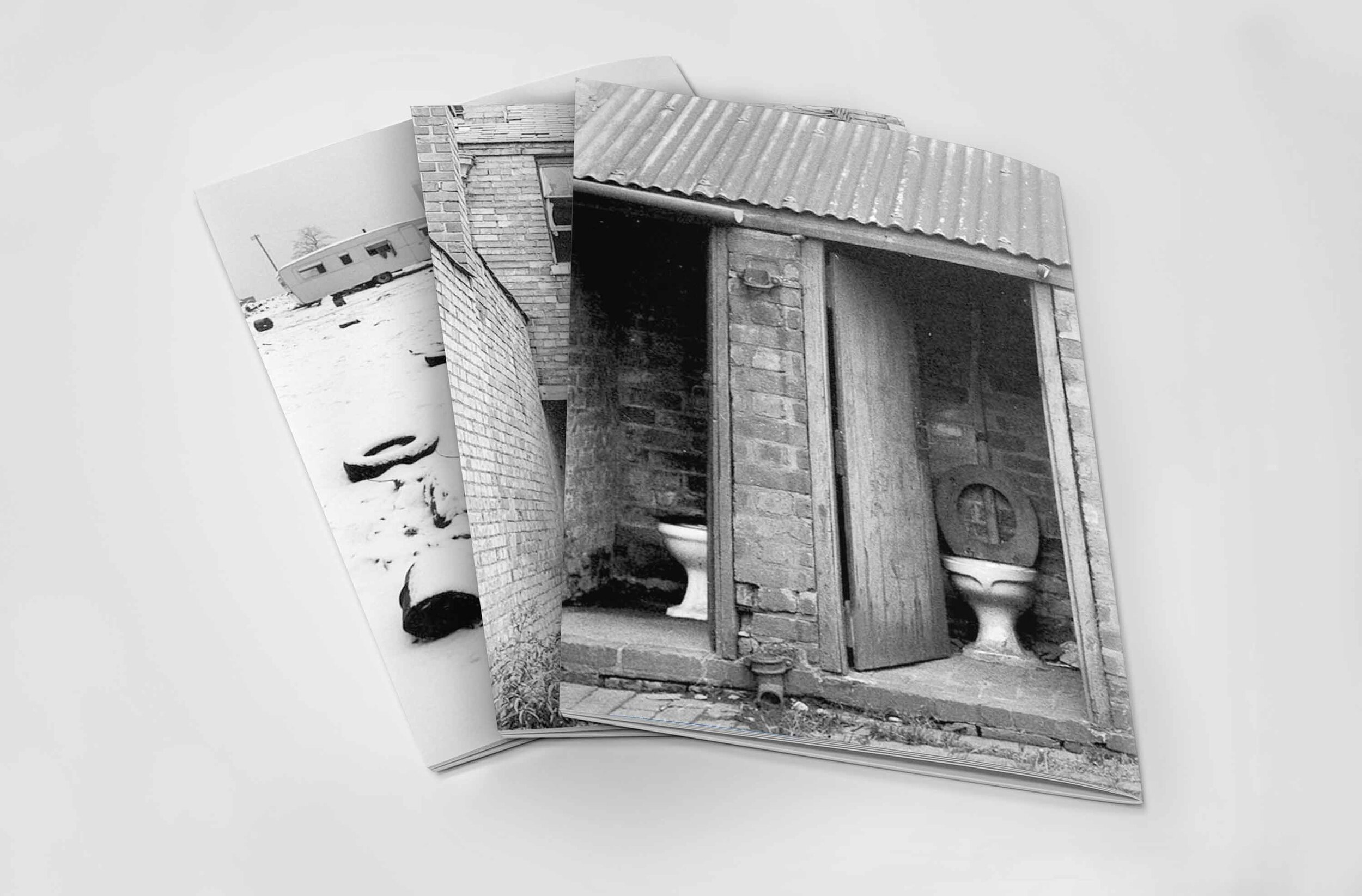

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

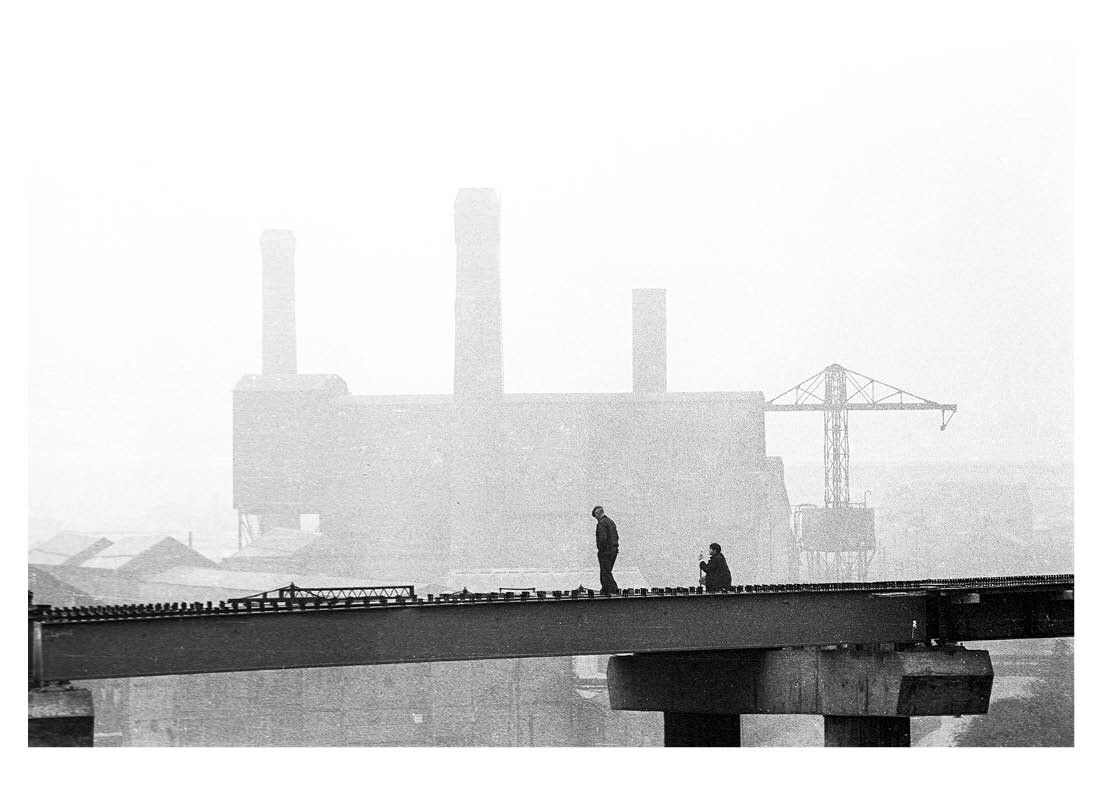

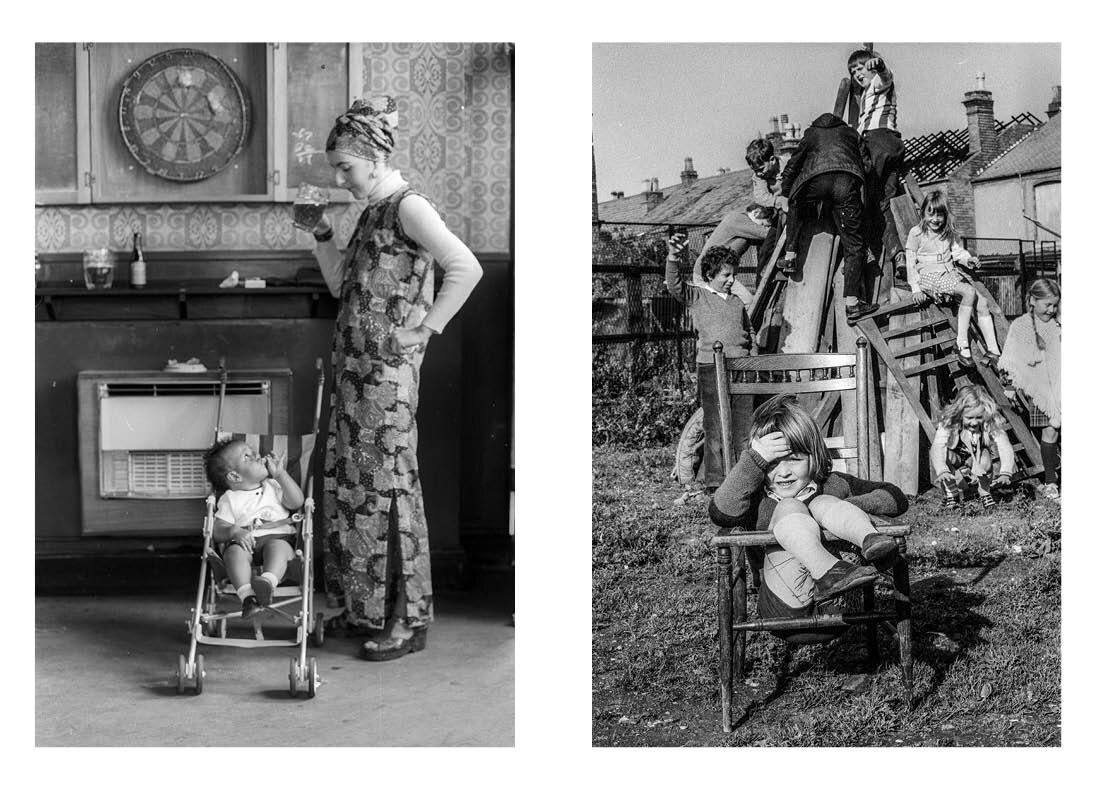

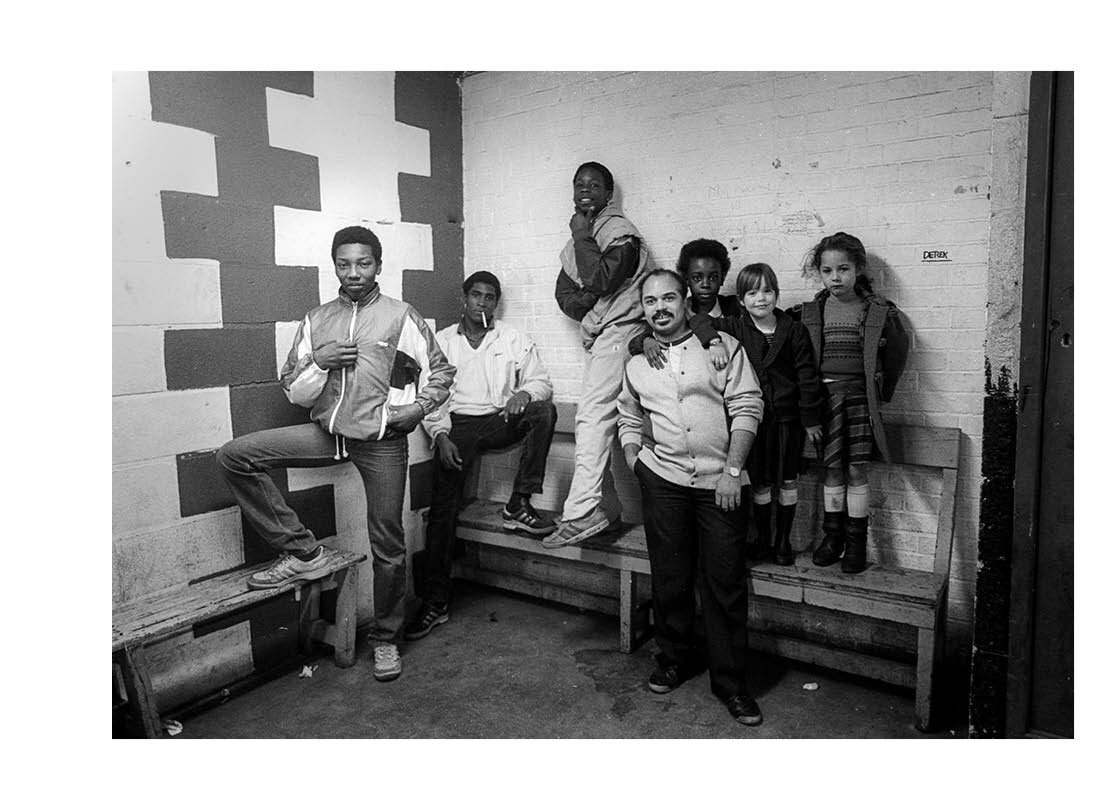

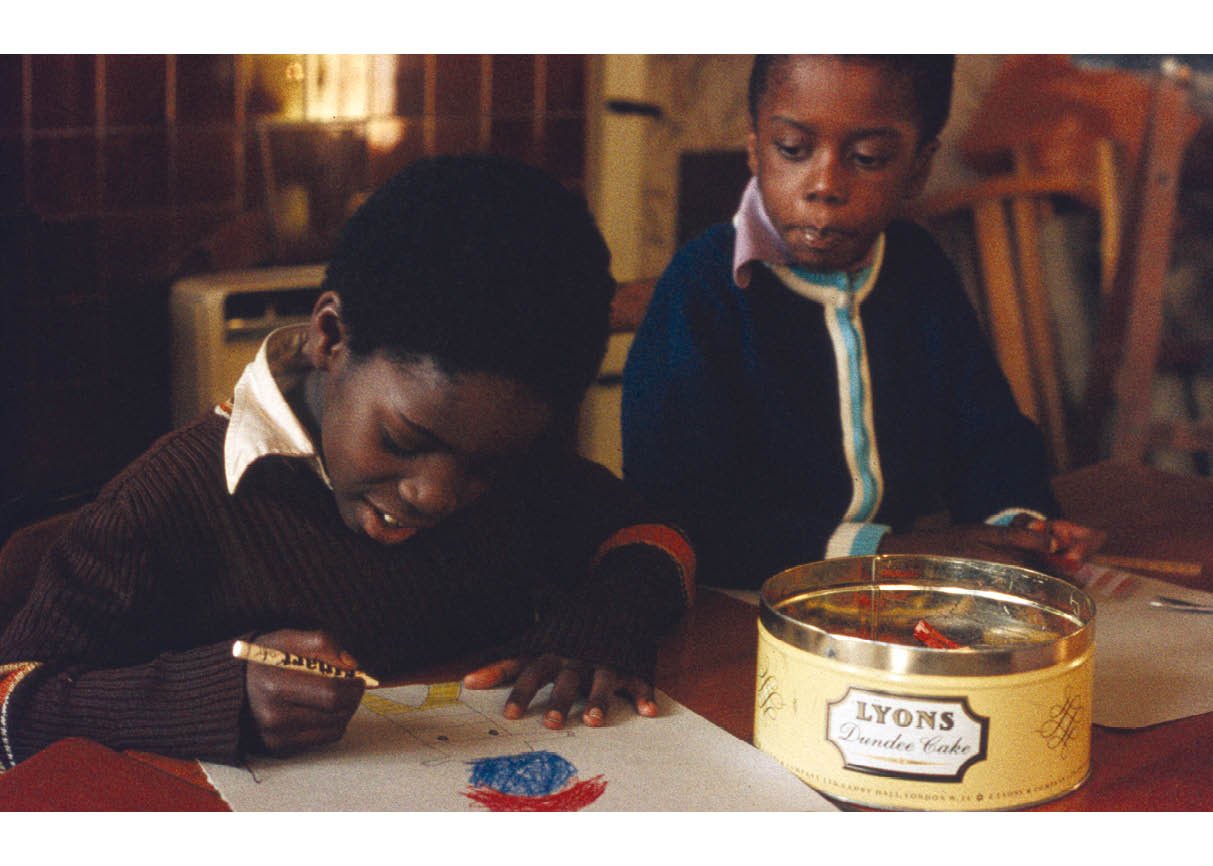

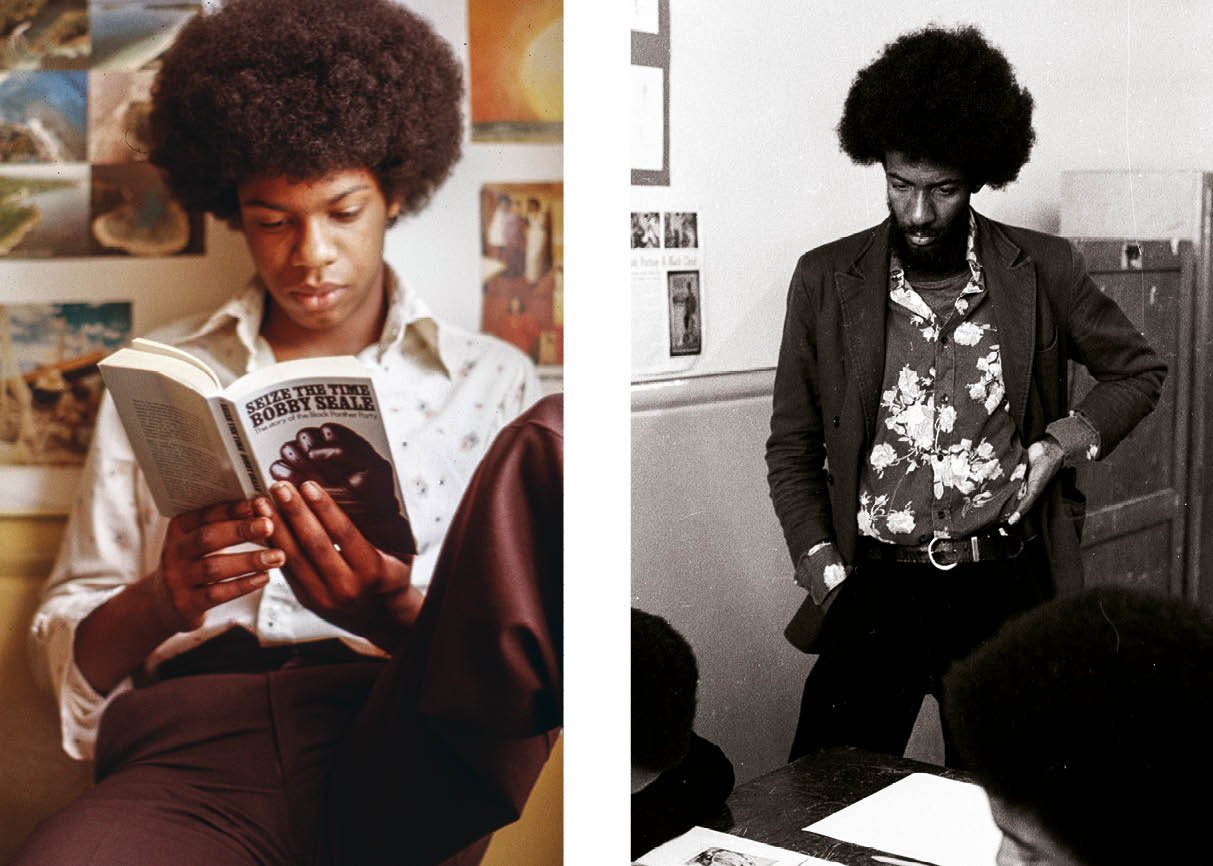

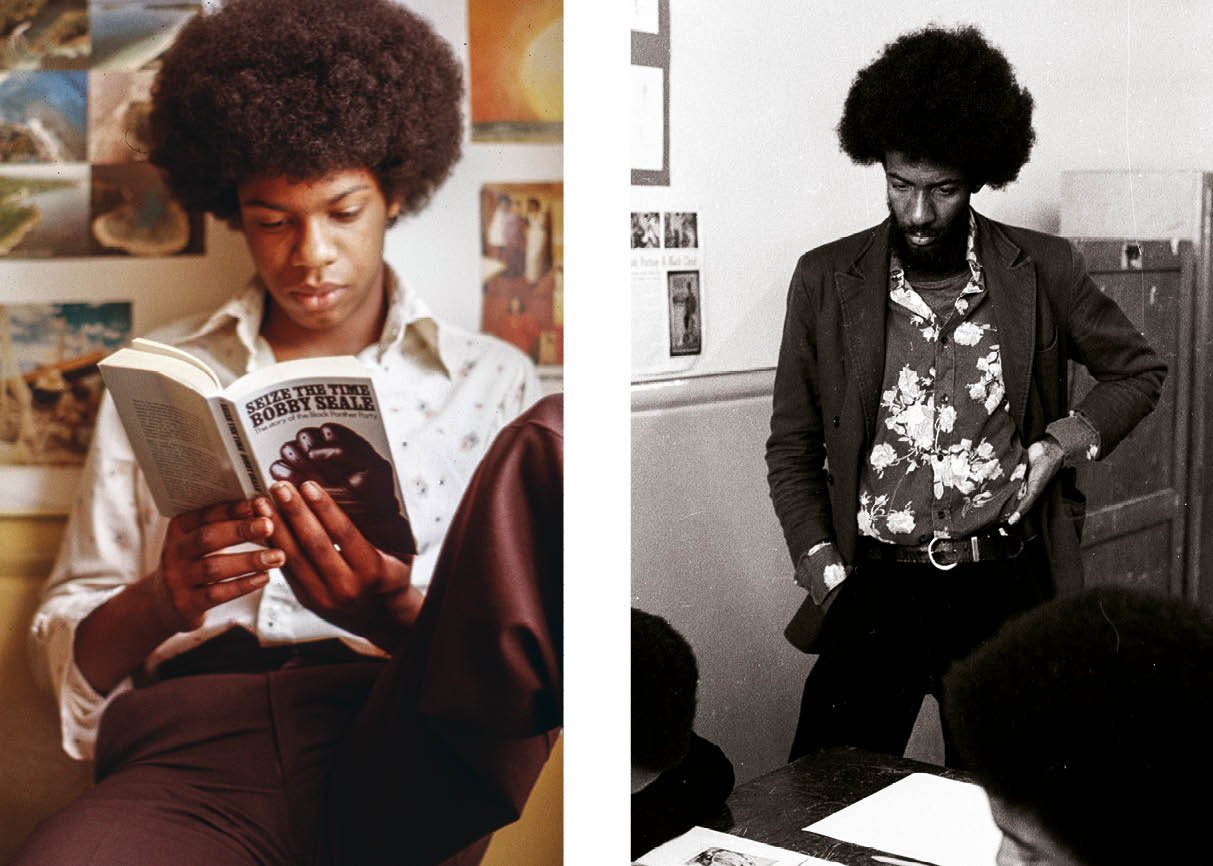

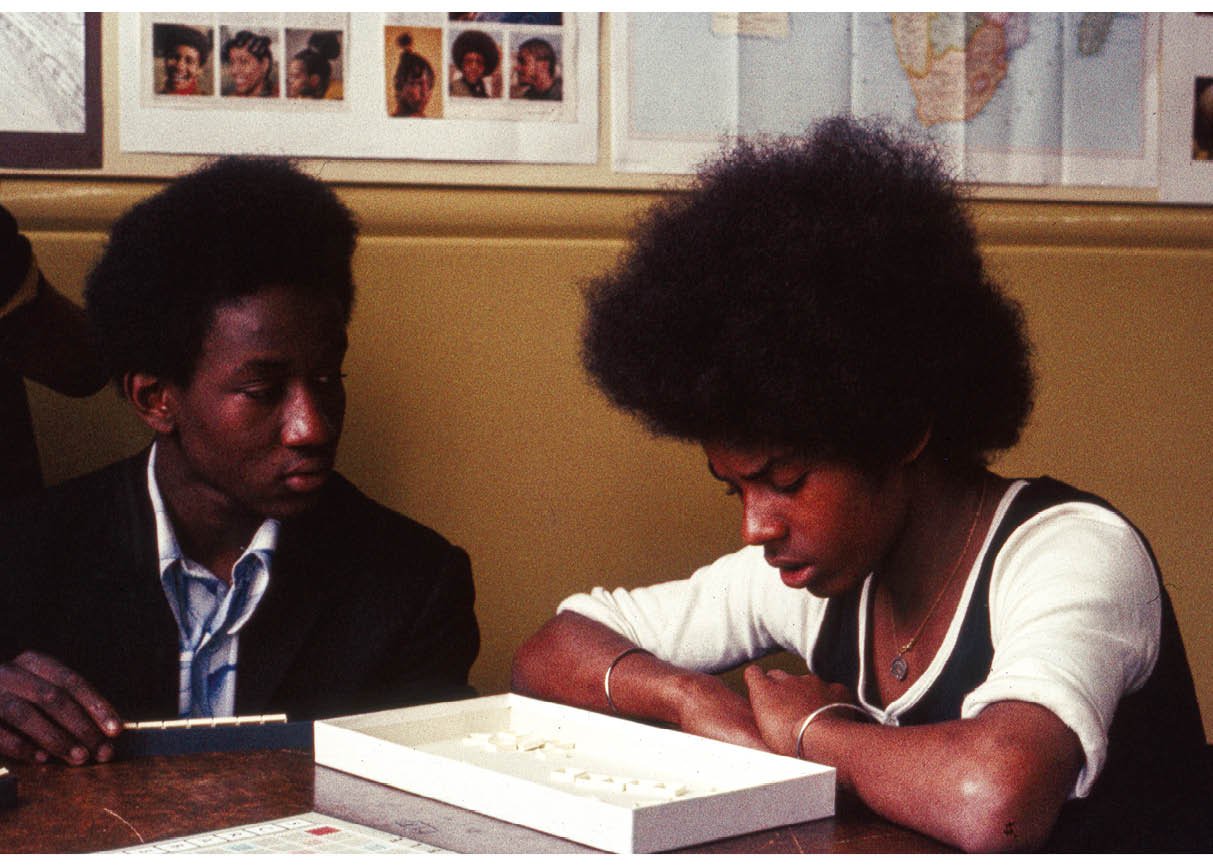

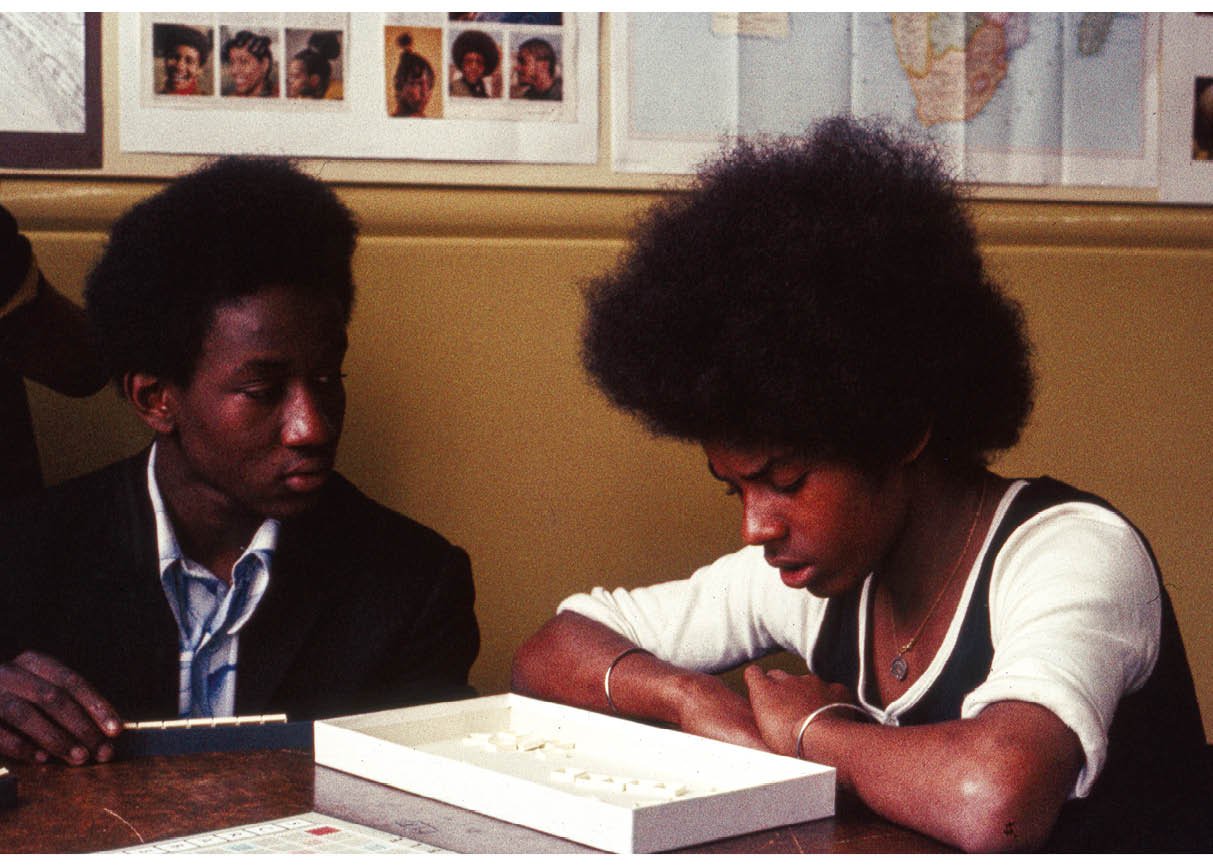

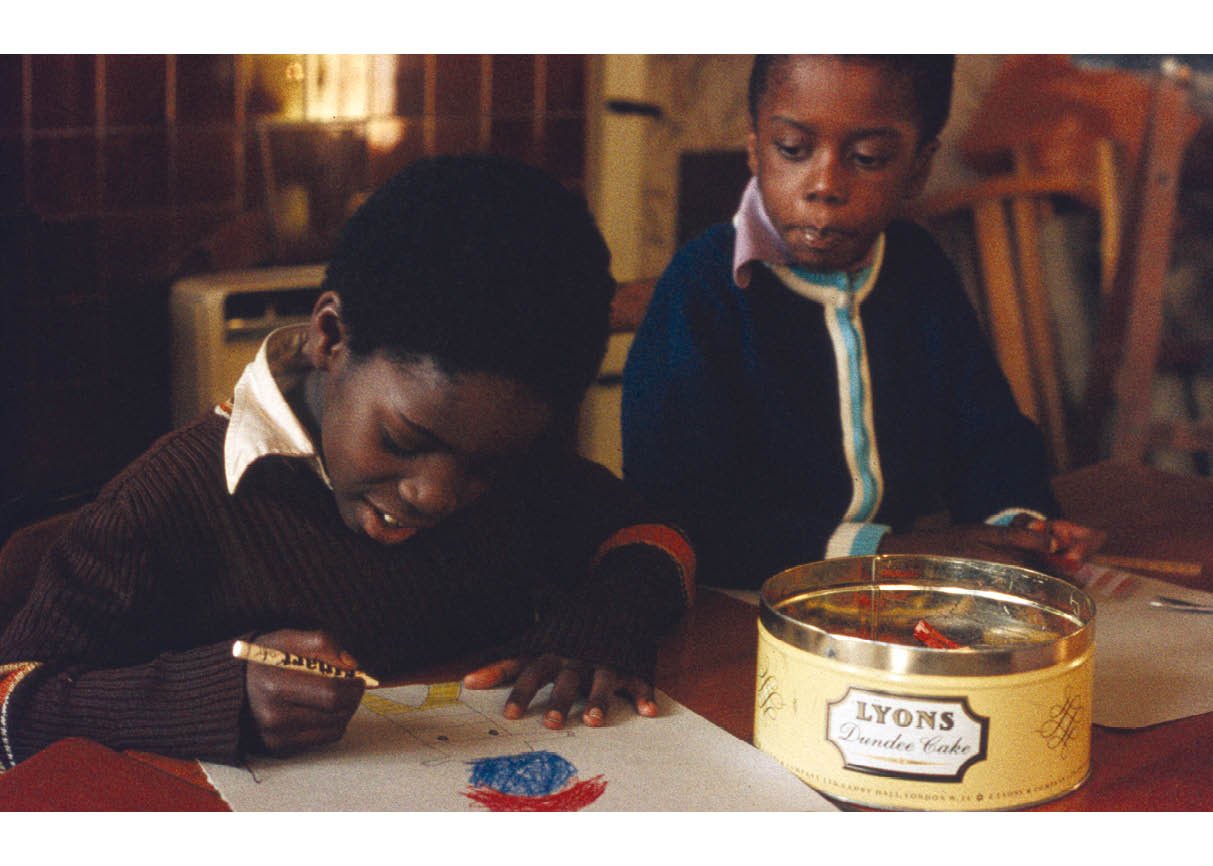

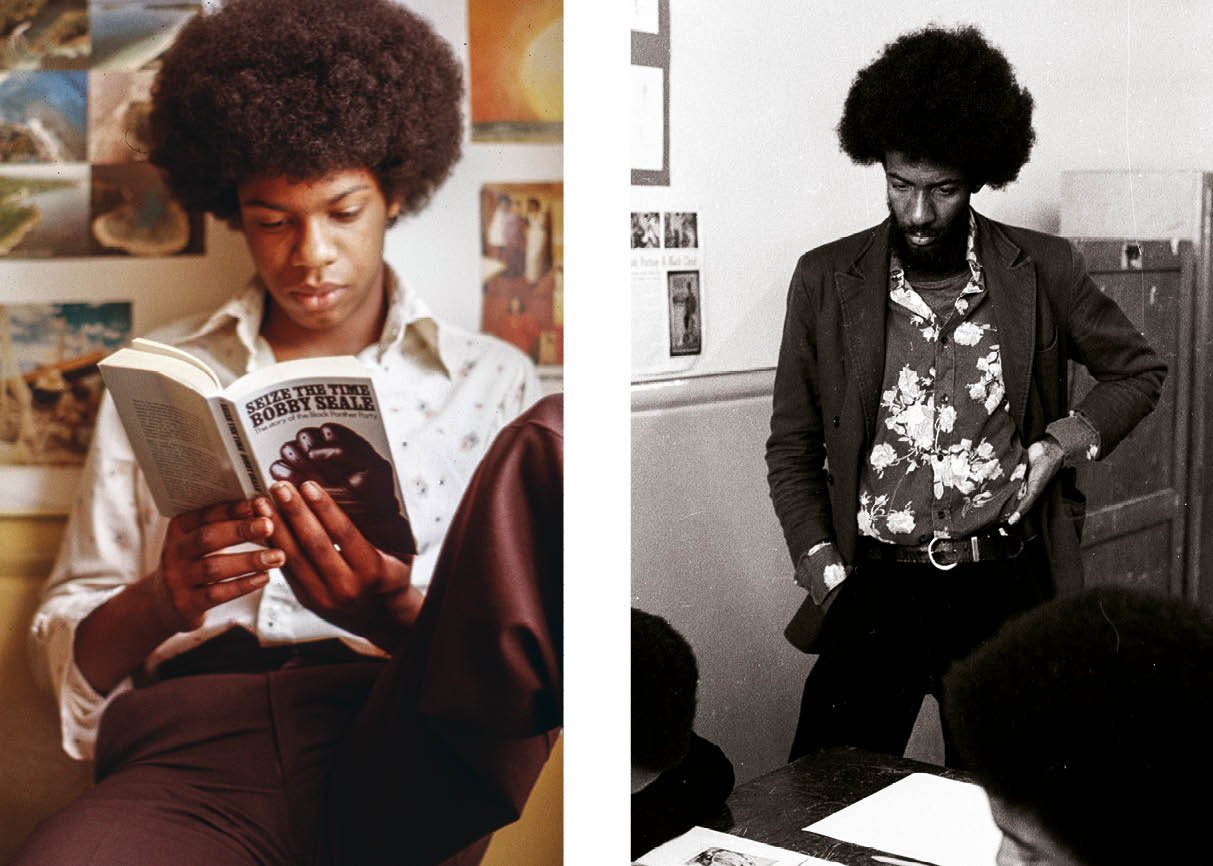

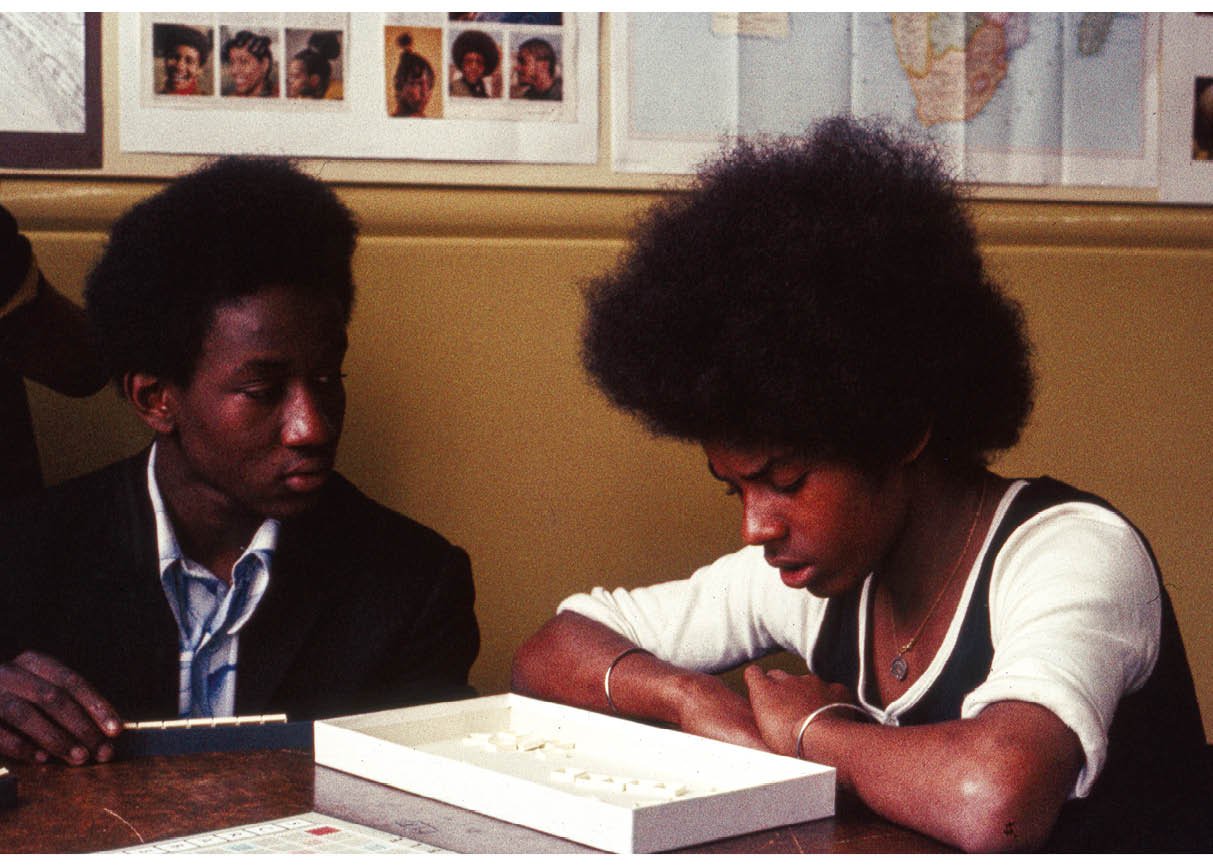

The London Borough of Waltham Forest’s West Indian Supplementary Service was an intervention to support children from families of Caribbean origin in the borough’s primary and secondary schools. Bernard Coard’s critique How the West Indian Child is made Educationally Sub-Normal in the British School System (1971) made a significant contribution to debates around the apparent relative failure of black children to thrive in mainstream education. Though not simply a response to Coard’s publication, the Supplementary Service aimed to enable black children to negotiate the demands of the school curriculum more successfully - by explicitly encouraging an understanding of language variation (dialects in relation to ‘standard’ English) and by teaching about Caribbean culture and black history. Most supplementary teachers worked with very small groups of children withdrawn from mainstream classes for short periods each day. With older students, provision was more flexible and could become more innovative, especially when mainstream classes were reduced following exams.

The photographs here were selected from two series. Some were taken at Downsell Junior School through November 1974 - February 1975. The building, a Victorian elementary school, no longer exists. Others were taken at Leyton Senior High School for Boys and at the headquarters of the Supplementary Service when a small group worked on a black school magazine - Uptight - in the Summer of 1975. The series runs from March to December 1975.

Originally the Supplementary Service addressed the needs of children brought over from the Caribbean at school age but, by the mid 1970s, they were a minority. Wayne Skeete was one of those born in the Caribbean - in Barbados. Looking back in 2023, he wrote: “I can’t say that school in Leyton provided me with the necessary tools for later life or developed my academic potential. Teachers went through the motions and didn’t show any inclination to engage in a meaningful way. All engagement was usually negative. For instance, I was pretty good at maths and the class that I and another friend (Ken Simmons) were initially assigned to was way below the level that we were used to, we repeatedly asked to be moved up but was denied. We eventually stopped going to the classes and ended up truanting. The West Indian Supplementary Service was a god send. I was exposed to a different literature, and my conscious was awakened by the struggles going on in America for the Afro American. It gave me an opportunity to work on a project (the school magazine) and developed a liking for writing and in particular poetry. On the social side I met people who I am still friends with today.”

Biographical note: I first taught with the West Indian Supplementary Service when I was twenty-two, in November 1974. I retired, from the University of London Institute of Education, in November 2013. This collection is in memory of Joyce Little (1938-2018) who was the ‘teacher-in-charge’ of the West Indian Supplementary Service when these photographs were taken.

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

The London Borough of Waltham Forest’s West Indian Supplementary Service was an intervention to support children from families of Caribbean origin in the borough’s primary and secondary schools. Bernard Coard’s critique How the West Indian Child is made Educationally Sub-Normal in the British School System (1971) made a significant contribution to debates around the apparent relative failure of black children to thrive in mainstream education. Though not simply a response to Coard’s publication, the Supplementary Service aimed to enable black children to negotiate the demands of the school curriculum more successfully - by explicitly encouraging an understanding of language variation (dialects in relation to ‘standard’ English) and by teaching about Caribbean culture and black history. Most supplementary teachers worked with very small groups of children withdrawn from mainstream classes for short periods each day. With older students, provision was more flexible and could become more innovative, especially when mainstream classes were reduced following exams.

The photographs here were selected from two series. Some were taken at Downsell Junior School through November 1974 - February 1975. The building, a Victorian elementary school, no longer exists. Others were taken at Leyton Senior High School for Boys and at the headquarters of the Supplementary Service when a small group worked on a black school magazine - Uptight - in the Summer of 1975. The series runs from March to December 1975.

Originally the Supplementary Service addressed the needs of children brought over from the Caribbean at school age but, by the mid 1970s, they were a minority. Wayne Skeete was one of those born in the Caribbean - in Barbados. Looking back in 2023, he wrote: “I can’t say that school in Leyton provided me with the necessary tools for later life or developed my academic potential. Teachers went through the motions and didn’t show any inclination to engage in a meaningful way. All engagement was usually negative. For instance, I was pretty good at maths and the class that I and another friend (Ken Simmons) were initially assigned to was way below the level that we were used to, we repeatedly asked to be moved up but was denied. We eventually stopped going to the classes and ended up truanting. The West Indian Supplementary Service was a god send. I was exposed to a different literature, and my conscious was awakened by the struggles going on in America for the Afro American. It gave me an opportunity to work on a project (the school magazine) and developed a liking for writing and in particular poetry. On the social side I met people who I am still friends with today.”

Biographical note: I first taught with the West Indian Supplementary Service when I was twenty-two, in November 1974. I retired, from the University of London Institute of Education, in November 2013. This collection is in memory of Joyce Little (1938-2018) who was the ‘teacher-in-charge’ of the West Indian Supplementary Service when these photographs were taken.