Image 1 of 19

Image 1 of 19

Image 2 of 19

Image 2 of 19

Image 3 of 19

Image 3 of 19

Image 4 of 19

Image 4 of 19

Image 5 of 19

Image 5 of 19

Image 6 of 19

Image 6 of 19

Image 7 of 19

Image 7 of 19

Image 8 of 19

Image 8 of 19

Image 9 of 19

Image 9 of 19

Image 10 of 19

Image 10 of 19

Image 11 of 19

Image 11 of 19

Image 12 of 19

Image 12 of 19

Image 13 of 19

Image 13 of 19

Image 14 of 19

Image 14 of 19

Image 15 of 19

Image 15 of 19

Image 16 of 19

Image 16 of 19

Image 17 of 19

Image 17 of 19

Image 18 of 19

Image 18 of 19

Image 19 of 19

Image 19 of 19

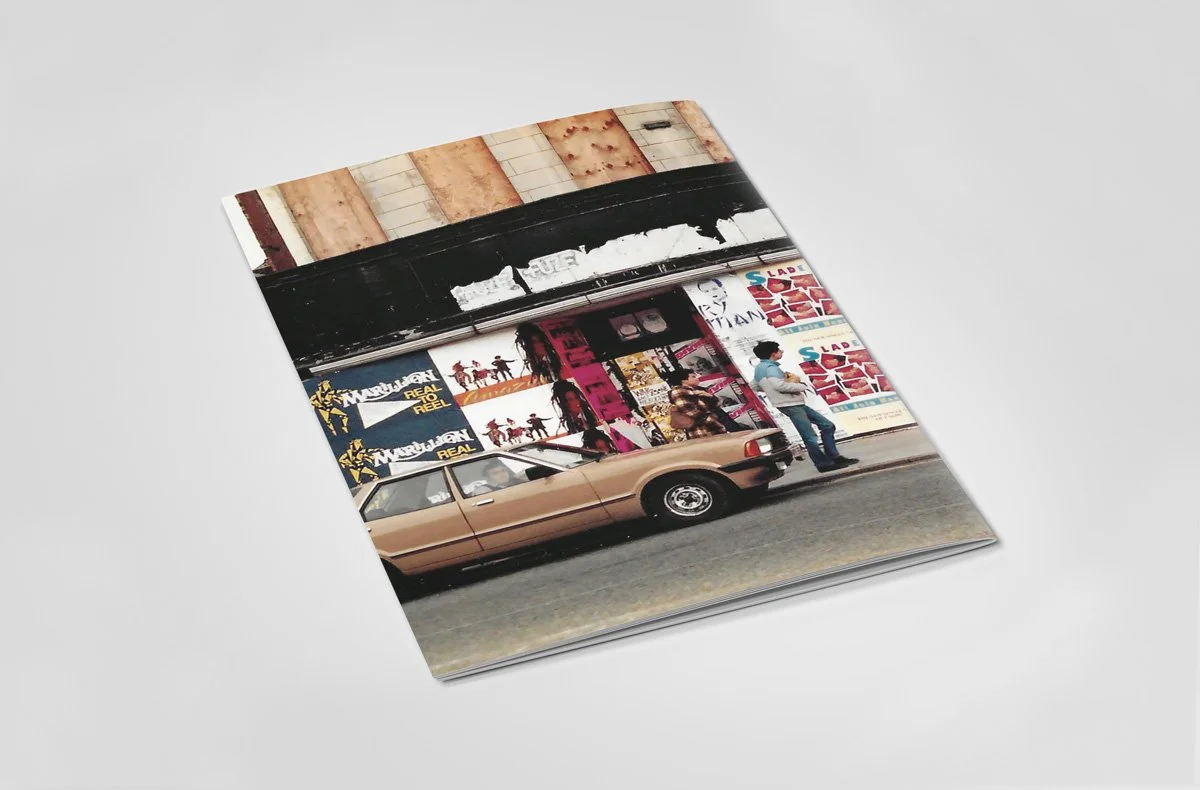

Caroline Coon — Nothing to Lose Punk 1970s

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

London 1975: the historical year the Sex Pistols began their shocking fight to be heard through the fog of stagnation and paralysing gloom that had fallen over the land. By winter 1976, they were heard loud and clear! The band, and the fans who immediately identified with them as representing the spirit of their new age, had caused a dramatic break with the past. There was horror in the music industry as older musicians and established record companies sensed they had lost control and were about to become outdated if not redundant. The mainstream media, reacting in moral panic to the “uproar”, “rock outrage” and the use of “the filthiest language heard on British television” called for the banning of everything and anything associated with punk.

Today, looking back at the photographs I took then, reminds us that all the musicians and fans creating such disruptive, universal perturbation were barely out of their teens: Johnny Rotten was just 20. Joe Strummer was 23. The average age of The Jam was 19, The Buzzcocks – 19, Subway Sect – 18. Poly Styrene, lead singer of X-Ray Specs, was 19, Ari-Up, lead singer of The Slits, was 14.

Over the last five decades, theoreticians in the cultural studies industry, historians, music critics and journalists have written enough about punk to fill an Atlantic trench. Every minute facet of the punk era has been forensically examined, loading on to the young shoulders of those who created it every conceivable expectation. A general theme has been a morose blaming of the musicians for not living up to their youthful aspirations.

However, I celebrate the success of punk, especially for the way that space was created for women and, as Ruth Adams (reader in Cultural and Creative Industries at Kings College) maintains: punk bands, with their support for Rock Against Racism, changed our white national identity by imagining “a multicultural, post-colonial future [...] which to a large extent has come to pass.”1

And, of course, we still listen to the exhilarating music in all its style and diversity!

1 Ruth Adams “‘Are you going backwards, Or are you going forwards’ – England past and England future in 1970s punk’”. Essay in ‘Working for the Clampdown: The Clash, the dawn of neoliberalism and the political promise of punk’ edited by Colin Coulter (Manchester University Press 2019), pp 89 – 104.

Caroline Coon

Nothing to lose. The punk photographs of Caroline Coon was shown at The Centre for British Photography 17.11.23–17.12.23

36 pages

printed in England

staple bound

14cm x 20cm

London 1975: the historical year the Sex Pistols began their shocking fight to be heard through the fog of stagnation and paralysing gloom that had fallen over the land. By winter 1976, they were heard loud and clear! The band, and the fans who immediately identified with them as representing the spirit of their new age, had caused a dramatic break with the past. There was horror in the music industry as older musicians and established record companies sensed they had lost control and were about to become outdated if not redundant. The mainstream media, reacting in moral panic to the “uproar”, “rock outrage” and the use of “the filthiest language heard on British television” called for the banning of everything and anything associated with punk.

Today, looking back at the photographs I took then, reminds us that all the musicians and fans creating such disruptive, universal perturbation were barely out of their teens: Johnny Rotten was just 20. Joe Strummer was 23. The average age of The Jam was 19, The Buzzcocks – 19, Subway Sect – 18. Poly Styrene, lead singer of X-Ray Specs, was 19, Ari-Up, lead singer of The Slits, was 14.

Over the last five decades, theoreticians in the cultural studies industry, historians, music critics and journalists have written enough about punk to fill an Atlantic trench. Every minute facet of the punk era has been forensically examined, loading on to the young shoulders of those who created it every conceivable expectation. A general theme has been a morose blaming of the musicians for not living up to their youthful aspirations.

However, I celebrate the success of punk, especially for the way that space was created for women and, as Ruth Adams (reader in Cultural and Creative Industries at Kings College) maintains: punk bands, with their support for Rock Against Racism, changed our white national identity by imagining “a multicultural, post-colonial future [...] which to a large extent has come to pass.”1

And, of course, we still listen to the exhilarating music in all its style and diversity!

1 Ruth Adams “‘Are you going backwards, Or are you going forwards’ – England past and England future in 1970s punk’”. Essay in ‘Working for the Clampdown: The Clash, the dawn of neoliberalism and the political promise of punk’ edited by Colin Coulter (Manchester University Press 2019), pp 89 – 104.

Caroline Coon

Nothing to lose. The punk photographs of Caroline Coon was shown at The Centre for British Photography 17.11.23–17.12.23